When Authority Replaces Conscience

How federal power, authoritarian obedience, and a culture of permission turned Minneapolis into a warning

Earlier today, January 24, federal immigration officers shot and killed a man in Minneapolis, the third such shooting in under a month. Hospital records confirm the man died from his injuries. On January 7, 2026, Minneapolis became the unlikely epicenter of a dramatic escalation in federal immigration enforcement under the second Trump administration, not merely in arrests, but in lethal force. The Hennepin County Medical Examiner later ruled Renée Good’s death a homicide from multiple gunshot wounds inflicted by a federal officer, Jonathan Ross. Different accounts of that incident emerged almost immediately, including federal claims that Good posed a threat and eyewitness accounts that sharply dispute that narrative, underscoring how quickly facts become contested in highly charged law-enforcement encounters.

What followed was extraordinary. Tens of thousands of Minnesotans engaged in protests, strikes, and economic blackouts, shutting down schools and workplaces, filling downtown streets, and standing for hours in sub-zero temperatures, demanding accountability and the withdrawal of federal agents. These demonstrations, organized under banners such as the Day of Truth & Freedom, were largely disciplined and controlled. Yet they were not met with de-escalation, but with expanding federal deployments, riot gear, chemical agents, and an increasingly militarized posture in residential neighborhoods.

Less than three weeks after Good’s death, on January 14, another federal officer shot a Venezuelan man in the leg during an enforcement action, triggering further protests and confrontations. Then came today’s killing.

Within hours, the Department of Homeland Security moved to define the incident on its own terms. In statements to the BBC and other outlets, DHS characterized the killing as “defensive,” asserting that the man was armed and “violently resisted,” and then quickly shifted to portraying protesters as aggressors who “obstructed and assaulted law enforcement.” The account did not address eyewitness claims that the man was already subdued when shots were fired, nor did it indicate whether body-camera footage exists or will be released. As in prior cases, federal leadership tried to settle the moral question before independent verification could catch up.

But the story refused to stay closed. The man was identified as Alex Pretti, 37, an ICU nurse at the Minneapolis VA. And bystander videos, analyzed by The New York Times, show him holding a cellphone as federal agents moved in, not a gun in his hand at the moment they took him to the ground and shot him.

This is the heart of the Minneapolis story now: not only that people are dying, but that federal authorities are racing the evidence, issuing a complete justification first and leaving the public to reconstruct what happened afterward.

Taken in isolation, individual uses of force by law enforcement, especially in operations involving armed suspects, are often framed as tragic but defensible. But none of these killings or protests would be occurring if ICE and other federal agents had not descended on Minneapolis in such a heavy-handed way, or if they simply had not been present at all. The massive deployment known as Operation Metro Surge sent thousands of armed DHS agents, including ICE and Border Patrol, into the Twin Cities for what the federal government described as immigration enforcement. That unprecedented surge dramatically expanded federal law-enforcement operations in the state and took place amid rising tensions and public distrust of the mission.

Taken together, in rapid succession, with escalating tactics and rhetoric, these uses of force form a pattern that cannot be explained as coincidence or rogue behavior. The shootings, the confrontations, the crowd control measures, and the cycle of action and reaction are the direct product of organizational culture, leadership incentives, and the ideological framing of enforcement priorities, not isolated outbursts.

At the center of this shift are figures such as Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem, Donald Trump, and immigration hard-liner Stephen Miller, whose influence on immigration policy predates Trump’s second term. Their leadership has reshaped federal immigration enforcement into a model that prizes maximum action over measured restraint. In the weeks following Good’s killing, Noem publicly doubled down on the operation, announcing hundreds more federal agents would be sent to Minneapolis even as protests mounted and local leaders demanded their withdrawal. She defended ICE officers reflexively and castigated journalists who questioned official narratives, reframing scrutiny itself as hostility.

This posture, dispatch more agents, expand operations, dismiss criticism, and portray dissent as threat, creates an organizational culture in which agents do not merely enforce laws; they internalize an us-versus-them worldview. When leadership defines communities, protesters, and even the press as antagonists, agents are primed to see force not only as permitted, but as required.

Psychologists who study authoritarian behavior have long described this mechanism in precise terms. In Conservatives Without Conscience, John Dean draws on decades of research by psychologist Bob Altemeyer on Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA), a personality and belief structure that reliably emerges in hierarchical, threat-oriented systems. Altemeyer identified three core traits that, taken together, explain how ordinary people come to participate in extraordinary harm.

The first is authoritarian submission: a deep psychological tendency to obey perceived legitimate authority figures, especially when those authorities claim to be acting in defense of order, security, or the nation. In this construct, legitimacy flows from position, not conduct. If an action is endorsed by leadership, it is assumed to be justified.

The second is authoritarian aggression: a learned willingness to harm others when authority signals that such harm is acceptable, necessary, or virtuous. Crucially, this aggression is not random or sadistic. It is selective and directional, aimed at those defined by authority as threats, outsiders, or enemies.

The third is conventionalism: rigid adherence to in-group norms, narratives, and moral frames. Complexity collapses. Dissent becomes deviance. Those who question authority are no longer participants in a shared civic project but obstacles to be overcome.

The central insight, and the most dangerous one, is that within this framework, the moral brake is externalized. People operating under authoritarian conditioning do not ask, “Is this right?” They ask, “Has authority sanctioned this?” Once the answer is yes, ethical judgment is no longer experienced as a personal responsibility. It has been transferred upward.

This is the moment where restraint becomes indistinguishable from disobedience, and conscience is reframed as weakness. Individuals no longer see themselves as moral actors making choices; they see themselves as instruments executing a settled mandate.

This dynamic was visible in the Watergate era, when figures like G. Gordon Liddy treated criminal acts not as moral transgressions but as duties once they were implicitly authorized by the Nixon White House. It was visible in post-9/11 counterinsurgency campaigns, where detainee abuse, civilian casualties, and collective punishment were rationalized as unfortunate but necessary components of a larger mission. And it appears starkly in Minneapolis today.

Federal agents operating in this environment are not weighing proportionality in the abstract. They are responding to a leadership culture that has already defined who is dangerous, who is legitimate, and what level of force is acceptable. Once that moral universe is constructed from above, the individual agent’s task is no longer to judge, only to comply or simply react.

History offers an even more sobering warning. The My Lai massacre during the Vietnam War is often misremembered as the work of uniquely cruel men. In reality, Lieutenant William Calley did not personally carry out every atrocity. What he did was more consequential: he authorized them. He defined civilians as enemies, framed violence as necessity, and conveyed that the moral decision had already been made. His men believed responsibility had been transferred upward, replacing conscience with compliance. This is the danger of authoritarian systems. They do not require sadism, merely permission.

For the protesters facing them in the street, these federal agents are no longer experienced as rational actors open to persuasion or restraint. They appear instead as functionaries executing a script, insulated from context, unmoved by appeal, and responsive only to command. This is not a failure of individual reason so much as the result of a system that has trained obedience to replace judgment.

The Minneapolis shootings must be understood through this lens. Agents operating under a leadership culture that frames immigration as invasion, protest as hostility, and accountability as persecution do not experience themselves as acting irrationally or impulsively. They experience themselves as fulfilling a mission. Like Lieutenant Calley’s men at My Lai, they believe the moral question has already been answered for them. Their certainty is not personal; it is institutional. And that certainty is what makes them so dangerous to confront — not because they lack belief, but because they possess it in excess.

The Minneapolis crisis is therefore not only about lethal force. It is about what happens when federal authority is politically amplified, imposed over local governance, and insulated from normal accountability. In Good’s case, official narratives claimed she was a threat; independent accounts and footage raised serious questions about proportionality. An FBI civil-rights inquiry was opened and then shifted. Calls for transparency, including body-camera footage, have been resisted.

In Iran, as documented recently in The New Yorker, security forces in Mashhad fired into crowds of demonstrators under cover of an internet blackout, killing hundreds, including children. Iranian authorities framed protesters as enemies of the state, criminals, even “enemies of God.” Officers carried out mass violence not because they were irrational, but because they were certain, certain they were defending order, certain leadership had sanctioned their actions, certain history would vindicate them.

Iran is not Minneapolis. The scale, system, and context differ profoundly. But the mechanism, moral authorization from above, is the same. And it is particularly chilling given that Donald Trump publicly claimed to support Iranian protesters even as federal forces under his leadership escalate violence against demonstrators at home. Authoritarian leaders can speak the language of freedom abroad while cultivating repression domestically, because what matters is not liberty but control over who is defined as legitimate, and who is defined as the enemy.

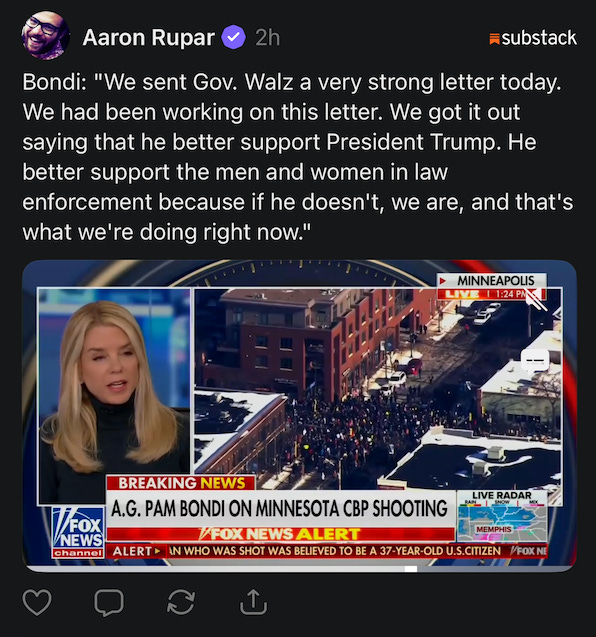

That authoritarian logic no longer needs to be inferred. It is now being spoken aloud. In a televised response to the Minneapolis shooting, Attorney General Pam Bondi made the terms unmistakable: Minnesota’s governor “better support President Trump” and “better support” federal law enforcement, or else. The implication was not subtle. Support is no longer a matter of constitutional obligation or lawful oversight; it is a test of loyalty. And if loyalty is withheld, force will proceed regardless.

This is precisely how authoritarian systems function. Authority is personalized. Law is subordinated to allegiance. Accountability is reframed as betrayal. In this framework, disagreement is not civic participation, it is defiance. Oversight is obstruction, and violence carried out in the leader’s name becomes self-justifying by definition.

For agents on the ground, this message matters more than any training manual. It tells them they will be defended not for acting lawfully, but for acting loyally. It tells them that escalation will be rewarded and restraint will be questioned. It tells them that the moral calculation has already been made, and that their job is not to judge, but to enforce.

This is how obedience replaces conscience. And it is why appeals to reason, legality, or shared norms fail in moments like this. The agents confronting protesters in Minneapolis are not negotiating a misunderstanding. They are executing a loyalty-bound mission in which dissent itself has been defined as the threat.

This is why the people standing in the cold in Minneapolis matter so much. Those brave souls are not merely protesting a policy, they are interrupting a trajectory. Authoritarian systems escalate until they are stopped. Atrocities do not arrive fully formed; they advance through normalization, silence, and fear. The first line of defense is always ordinary people who refuse to be terrorized into compliance, who insist on visibility, accountability, and moral friction before the worst becomes possible.

If the stated goal of enforcement is public safety, this strategy has failed spectacularly. What it has produced instead is fear, mistrust, and violence, and federal agents convinced that righteousness flows from authority rather than conscience. When resistance is treated as threat and certainty replaces judgment, cruelty no longer feels like cruelty, it feels righteous.

At its core, the crisis in Minneapolis is not about isolated shootings, but about what happens when policy directives, political rhetoric, and organizational culture converge to create behavior that is callous in execution and insulated from consequence. It is about the danger of power without prudence, authority without accountability, and enforcement without empathy. When leaders choose confrontation over consent, they do not merely enable violence, they are designing the conditions for it.

There is a free video called Genocide in a Suit (genocideinasuit.com) that covers the work of Gregory Stanton, founder of Genocide Watch. He is a Research Professor in Genocide Studies and Prevention, Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution, George Mason University

Genocide is not only the immediate killing of people. It can be a long, bureaucratically masked, legally “correct” and psychologically sophisticated process.

Before the obvious genocide are 8 preparatory stages:

I. Classification

II. Symbolization

III. Discrimination

IV. Dehumanization

V. Organization

VI. Polarization

VII. Preparation

VIII. Persecution

IX. Extermination

Excellent analysis. And accurate. We’re there.