The Price We Pay When Doubt Becomes Policy

Autism deserves support, not scapegoats, and America deserves prevention, not doubt

A parent sits on crinkled paper in a pediatrician’s office, one knee bouncing, a toddler’s sock half-off and dangling. The nurse has already taken the weight, height and the temperature. The doctor steps in with a smile that tries to be reassuring, but the smile catches, just for a second, because the next line isn’t medical. It’s political, procedural, confusing. “There’s been a change,” the doctor says, and suddenly the room feels smaller.

For decades, the childhood vaccine schedule functioned like quiet architecture: unseen until it isn’t there. Most families didn’t need to memorize it any more than they needed to memorize building codes. You showed up, asked questions, consented, and then you left with your child protected from the kinds of illnesses that used to haunt every neighborhood, every classroom, and every summer.

Now, the schedule has been reorganized. On January 5, 2026, federal health officials announced that the CDC would narrow what it routinely recommends for all children, shifting the schedule into categories, including a new emphasis on “shared clinical decision-making,” and listing routine immunization for protection against 11 diseases rather than the broader set previously recommended.

That phrase, “shared clinical decision-making,” sounds collaborative. It sounds empowering, but for many families, it lands like an extra bill slipped under the door. Because “shared decision-making” assumes time, health literacy, stable access to a trusted clinician, the ability to take off work, to return for follow-up doses, the ability to navigate insurance phone trees, to say, “I need another appointment,” and not risk losing your job. When public-health experts warn that sudden schedule revisions can erode trust and reduce uptake, they’re not talking about theory. They’re talking about the real-world friction that turns good intentions into missed shots.

This is how preventable diseases return: not only through loud refusal, but through quiet hesitation, and uncertainty. Through families who would have said yes yesterday and now say, “Maybe later,” because the most powerful health agency in the country made it sound like later would be just as safe.

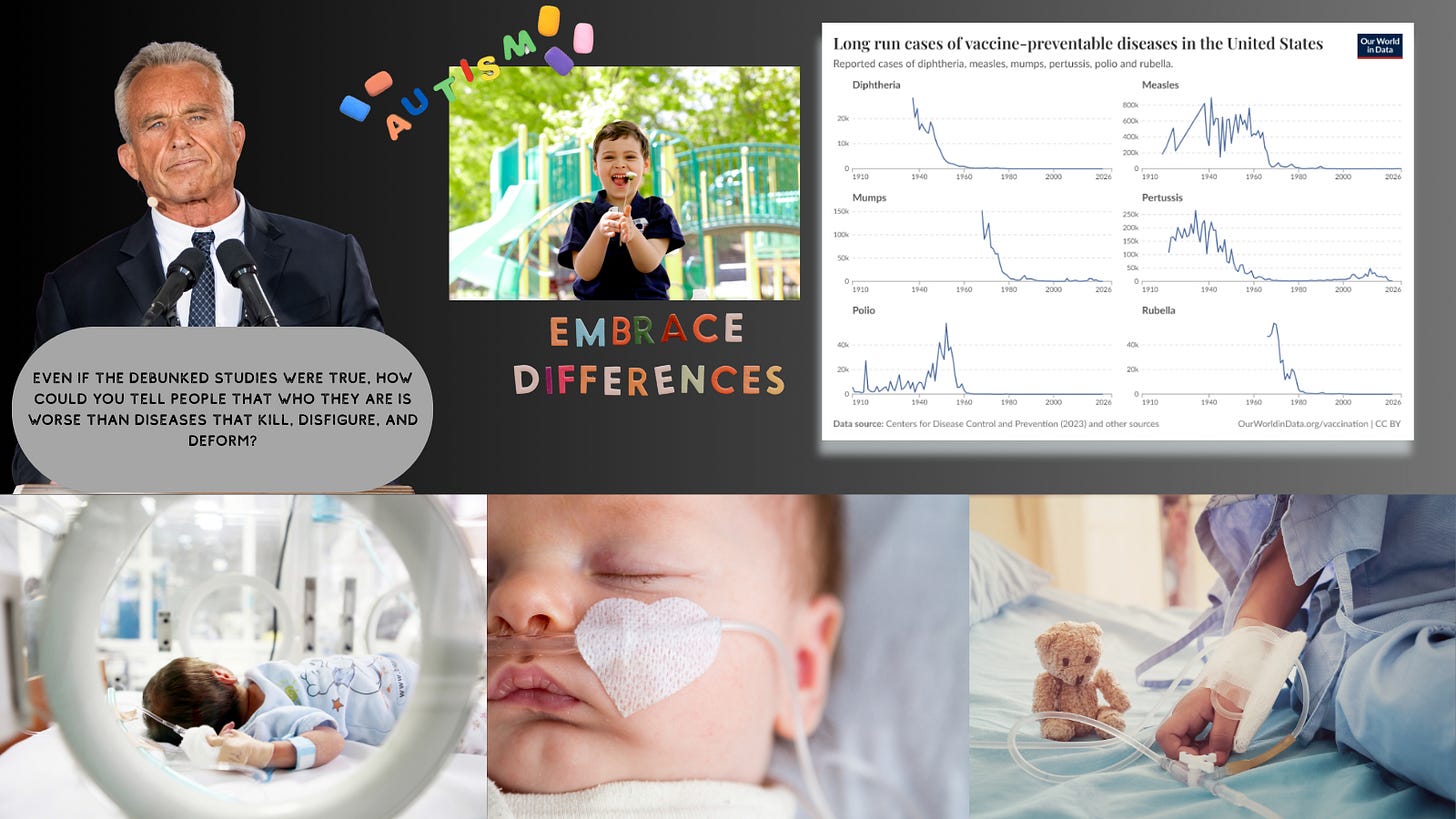

And this confusion doesn’t exist in a vacuum. In late January, reporting revealed that Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. had reshaped the federal autism advisory committee (the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee) with 21 new public members, including individuals described as having promoted or aligned with the long-debunked idea that vaccines cause autism. That kind of appointment isn’t a footnote; it’s a signal. It tells the public which questions are “serious,” which doubts deserve oxygen, and which conclusions can be reopened, no matter how many times the evidence has already answered them.

That signal grew louder in November 2025, when the CDC changed its own vaccine-safety messaging to imply that the statement “vaccines do not cause autism” is not evidence-based because studies have not “ruled out” the possibility of a link. This was not accompanied by a scientific earthquake, no new discovery that forced medicine to redraw the map. Instead, major scientific and medical voices pushed back: the World Health Organization’s vaccine safety committee reaffirmed, after reviewing evidence through August 2025, that there is no evidence of a causal relationship between vaccines and autism. The National Academies warned that CDC citations lacked crucial context and emphasized the overwhelming body of vaccine-safety work. The American Academy of Pediatrics has continued to state plainly that there is no credible link, and that the original spark of the MMR-autism claim came from research later retracted for fraud.

So, when families sense a coordinated drift, committee appointments that validate suspicion, federal webpages that reframe settled science as unsettled, and a vaccine schedule that shrinks what is routinely recommended, they aren’t being hysterical. They are noticing the weather change.

And we should talk honestly about what that weather brings.

Vaccines are not abstract, they are not “shots” in the vague way that word gets thrown around online, as if we’re debating a lifestyle choice. Vaccines are the reason most of us have never had to watch a child fade behind an oxygen mask from measles pneumonia, or develop encephalitis that steals speech and movement, or die from a fever that started as a rash. Before measles vaccination, the CDC estimates 3 to 4 million people in the U.S. were infected each year, and among reported cases, 400 to 500 people died annually, 48,000 were hospitalized, and 1,000 suffered encephalitis.

Vaccines are the reason we speak about polio in black-and-white photos: children in leg braces, wards lined with iron lungs, pools closed in summer because parents were terrified of water. Polio peaked in the U.S. in 1952 with more than 21,000 paralytic cases, according to CDC’s Pink Book. This is what “bring it back” means, not a nostalgic return to “natural immunity,” but a return to paralysis and funerals.

Vaccines are the reason congenital rubella syndrome is no longer a routine nightmare. During the 1962–1965 rubella epidemic, the CDC reports an estimated 12.5 million cases in the U.S., with 11,250 fetal deaths, 2,100 neonatal deaths, and 20,000 infants born with congenital rubella syndrome, often involving blindness, deafness, and heart defects. When you weaken trust in vaccines, you are not merely “asking questions.” You are flirting with the conditions that made those numbers possible.

Even the diseases people dismiss as “mild” were never mild for everyone. Chickenpox used to be a rite of passage people joked about, until you look at the CDC’s own history: in the early 1990s, before the U.S. vaccination program, there were more than 4 million cases each year, 10,500 to 13,500 hospitalizations, and 100 to 150 deaths, about half in children.

And then there are the diseases that don’t always make headlines because they don’t arrive with a dramatic name, just a child who won’t stop vomiting, a sunken fontanelle, a dehydration spiral that turns fast. Before routine rotavirus vaccination, CDC estimates rotavirus caused 55,000 to 70,000 hospitalizations and 20 to 60 deaths each year among U.S. children under five. That’s not a philosophical debate, that’s an ICU bed you never should have needed.

Or meningococcal disease, the kind that can take a healthy teenager to the edge of death in hours. CDC notes that 10 to 15 in 100 people with meningococcal disease die, and one in five survivors lives with long-term disabilities that can include brain damage, deafness, or limb loss. There are parents who can tell you what it looks like when “a fever” becomes an amputation decision. There are survivors who carry the scars into adulthood.

This is what makes the current moment so painful: the stakes are not theoretical, but the messaging has become slippery, as if we’re all just consumers picking add-ons. Under the revised federal schedule, six vaccines are no longer routinely recommended for all children, rotavirus, influenza, COVID-19, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and meningococcal vaccines, shifted instead to narrower categories and “shared clinical decision-making.” In response, the American Academy of Pediatrics released its own 2026 schedule, continuing to recommend routine immunization to protect children against 18 diseases, including RSV, hepatitis A and B, rotavirus, influenza, and meningococcal disease. When pediatricians feel compelled to publish a parallel schedule for the first time in a generation, it’s because they can see what confusion costs in the clinic: delayed protection, missed windows, and outbreaks that start in pockets and spread into schools.

Yes, federal officials have said vaccines remain covered without cost-sharing. But access on paper is not the same as access in life. A recommendation is more than a suggestion; it is a cultural cue. It tells parents what is normal. It tells clinicians what is supported. It tells insurers and pharmacies what can be streamlined. When you downgrade routine recommendations, you don’t merely shift paperwork, you shift momentum.

And then, layered on top of all this, comes the rhetoric of “fighting autism.” Autism is not a virus, autism is not something you catch from a classmate’s cough, autism is a diagnosis that describes how a brain develops and processes the world. It can come with profound disability for some people and extraordinary strengths for others, and for many it is both, needs and gifts braided together in ways outsiders rarely see.

If our national mission is truly to support autistic people and their families, then we should pour resources into what helps: early supports and therapies that respect dignity, communication access, inclusive schools, respite care, adult services, employment pathways, housing, healthcare that actually meets autistic patients where they are. We should fight for autistic lives to be livable and safe.

But when “fighting autism” becomes entangled with resurrecting the vaccine-autism myth, when committees are stocked with people who treat a debunked suspicion as destiny, and when official messaging implies the question is still open, the mission curdles. It stops being about support and starts being about blame.

And blame always needs a target. For years, that target has been vaccination, one of the most studied public-health interventions in human history. The WHO reaffirms vaccines do not cause autism. The AAP reiterates the lack of a credible link. The National Academies caution against misusing the scientific record. Yet the narrative persists because it offers something seductively simple: a culprit you can point at, a story you can tell yourself about control, but control is not the same as truth.

Here is the moral crossroads America is staring at: if you elevate the fear of autism above the fear of diseases that kill, blind, disfigure, and disable, you risk teaching the country, quietly, implicitly, that an autistic child is a catastrophe worse than a child in a hospital bed. You risk telling autistic people, in the language of policy, that their existence is a public-health emergency, while measles and meningitis are optional. That is not compassion, that is stigma dressed up as concern. And it is also, in the most literal sense, dangerous.

Because the diseases vaccines prevent do not negotiate. They don’t care what you “believe.” They only care how many susceptible bodies they can find, they exploit gaps, and confusion creates gaps. And confusion itself is a kind of contagion. It spreads from a federal webpage into a family group chat, from a committee roster into a late-night scroll. From a change in recommendation into a postponed appointment, and then, one day, it spreads into a daycare classroom, a high school hallway, a neonatal unit.

What makes this moment so heartbreaking is that it is avoidable. We have been here before, and we fought our way out with science, with collective action, with the hard-earned knowledge that children’s graves should not be normal. When leaders choose doubt as a public-health strategy, when they re-litigate settled questions and shrink routine protections, they are not just “asking questions.” They are writing a future in which more parents will learn, too late, what measles looks like in a child’s eyes, what meningitis does to a limb, what rotavirus does to a tiny body that can’t hold onto water. If that future arrives, it will not arrive with a single dramatic decree. It will arrive the way so many tragedies do: one “maybe later” at a time. And then one day, we will look back at the crinkled paper in that pediatrician’s office and realize what was taken from us wasn’t just a schedule. It was certainty. It was trust. It was the quiet miracle of prevention, so ordinary we forgot it was a miracle at all.

I wrote a letter to NYTimes before I read this. Yes, how can we equate the ravages of polio with autism, which isn't terrible. My father wrote in 1932 after watching children suffer from polio. He said, "

"Of all the experiences that the physician must undergo, none can be more distressing than to watch respiratory paralysis in a child ill with poliomyelitis — to watch him as he becomes more and more dyspneic, using with increasing vigor every available accessory muscle of neck, shoulder and chin, silent wasting no breath for speech, wide-eyed and frightened, conscious almost to the last breath.”

Please, never again!

I was a little kid when my cousin was diagnosed with polio, but I can still remember the horror in my grandmother's eyes as she told us. When the vaccine first became available, my mother hurried my sister and me in for the"shot". Since early on there was no long history of reactions, she opted to have us vaccinated on our legs and not our arms. She figured that if something went wrong at the injection site, we could lived our lives better without a leg than without an arm. Thankfully, my cousin had only a mild case of polio, and he went on to play college football. My sister and I are both still walking on two legs. My mother correctly decided that the risks of the disease were worse than the risks, IF ANY, of the vaccination.