The Price We Paid to Live Long Enough to Forget

A long history of vaccination and how it rewrote human fate, written by Shanley Hurt.

As the CDC continues to revise its vaccine recommendations, particularly the immunization schedule for children, I feel compelled to speak out. It is gut-wrenching to watch a country that was once considered exceptionally safe, and largely free of vaccine-preventable diseases, now grapple with measles outbreaks. Even more distressing is the reality that many of these outbreaks are driven by unvaccinated individuals who have bought into misinformation being amplified at the highest levels of government. That this rhetoric is associated with figures like Robert F. Kennedy Jr., someone who is somehow treated as credible on public health matters, only deepens the concern.

But before we dive into the heartbreaking truths behind this resurgence in preventable disease, let’s first take a walk through history to gain some light on why vaccines have been such a prevalent and essential part of our lives.

In the 1950s, polio was one of the most feared diseases in America. Each year, it paralyzed more than 15,000 people and killed an average of 1,800, its victims included former President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Entire communities lived in dread of summer. Swimming pools were shuttered, parents kept children indoors, and hospital wards were filled with iron lungs.

That fear began to lift in 1955, when Dr. Jonas Salk’s Inactivated Poliovirus Vaccine (IPV) was licensed. The impact was swift and unmistakable. Following its licensure on April 12, 1955,

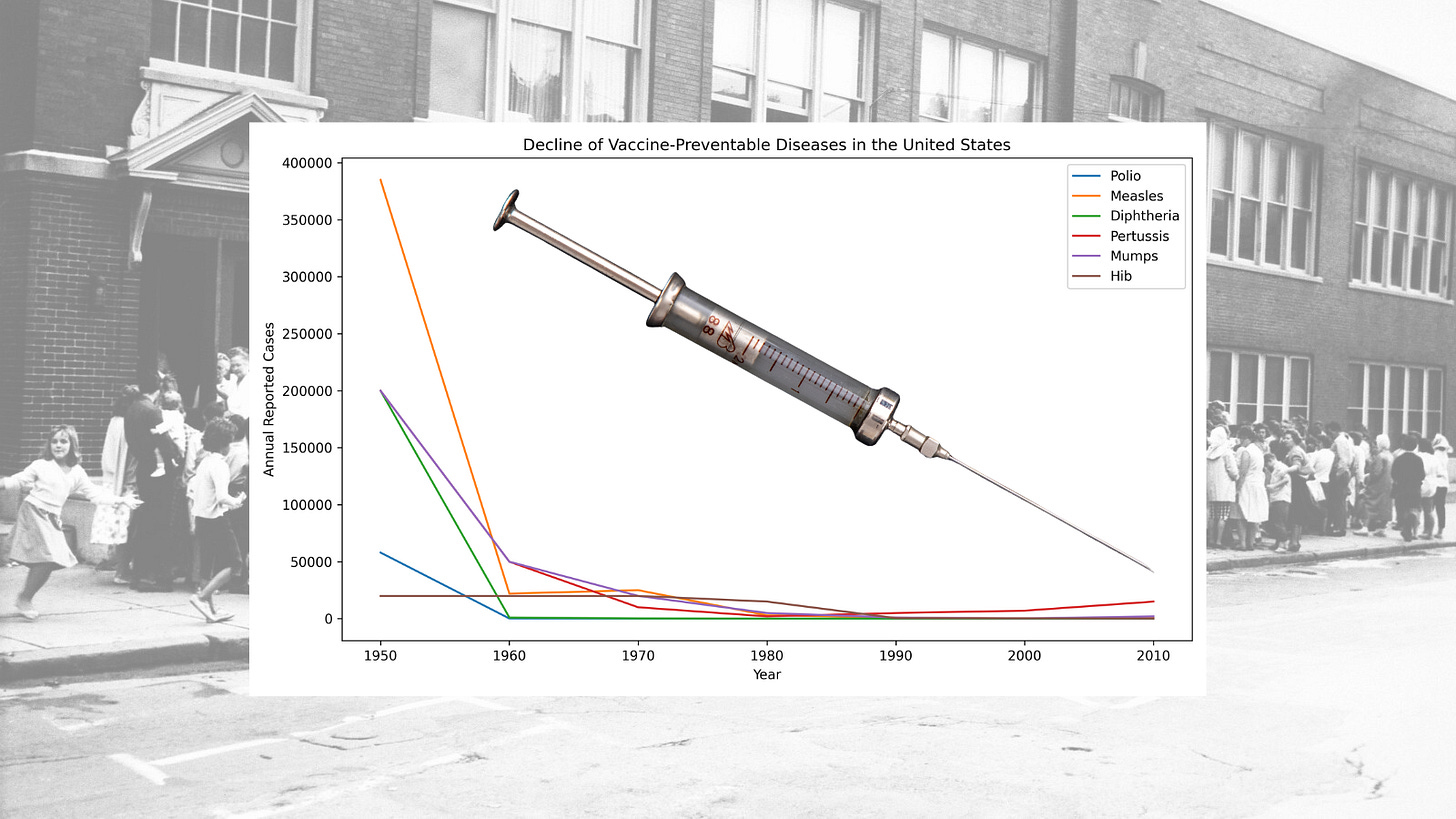

reported polio cases fell from roughly 29,000 in 1955 to 14,647 in 1956. Just two years after mass vaccination began, annual cases had plummeted by nearly 90% from their pre-vaccine peak, dropping to just 5,600. Within a single year of licensure, deaths attributed to polio declined by 50%. By 1961, only 161 cases remained in the United States, a staggering 99% reduction from the 1952 peak of approximately 58,000 cases.

The rapid success of the polio vaccine was not accidental. It was driven by widespread public need, collective action, and an unprecedented commitment to mass vaccination. In 1954, more than 1.8 million children, known as the “Polio Pioneers”, participated in massive field trials, their parents volunteering them in the hope of sparing future generations from paralysis. That spirit carried directly into 1955, when Americans stood in long lines to receive the newly approved vaccine. By August of that year, more than 4 million doses had already been administered.

The later introduction of Albert Sabin’s Oral Poliovirus Vaccine (OPV) accelerated the final push toward elimination. By 1979, polio was officially eliminated in the United States, not through doubt or delay, but through science, trust, and collective resolve.

In the 1950s and 1960s, measles ran rampant across the United States. A highly contagious virus and a leading cause of brain swelling due to encephalitis, measles infected an average of 500,000 Americans each year. Nearly every child was exposed. Hospitals filled with young patients suffering from high fevers, pneumonia, and neurological complications, and for many families, measles was not a routine childhood illness but a terrifying gamble.

A turning point came in January 1954, when Dr. Thomas Peebles, working in the laboratory of Dr. John Enders, often called the “father of modern vaccines”, at Boston Children’s Hospital, successfully isolated the measles virus from blood samples collected during an outbreak at a boys’ boarding school. The virus was cultured from an 11-year-old boy named David Edmonston. With foundational contributions from virologist Dr. Samuel Katz, this specific isolate, later known as the “Edmonston strain”, became the basis for nearly every measles vaccine that followed.

By 1958, Enders and his team had developed a live-attenuated version of the virus. From 1958 through 1960, the experimental vaccine was tested in small groups of children. Between 1960 and 1961, trials expanded dramatically, enrolling thousands of children in New York City and Nigeria. By 1961, the vaccine was being hailed as 100% effective in these large-scale studies. In 1963, the first two measles vaccines, a live-attenuated version known as “Edmonston-B” and an inactivated vaccine, were licensed for public use in the United States.

The public response was swift. By mid-1966, nearly 15 million children had been vaccinated, and reported measles incidence fell by 50% within the first three years. A nationwide mass-vaccination campaign from 1967 to 1968 accelerated the decline even further, reducing reported cases by 90% within just two years. By 1968, annual measles cases had dropped from 385,000 in 1963 to just 22,000.

That same year, an improved measles vaccine developed by Dr. Maurice Hilleman, one that significantly reduced post-vaccination fevers, was licensed and remains the standard in the United States today. Hilleman later combined the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines into a single MMR shot, licensed in 1971. In the decade before vaccination, measles caused an average of 500 deaths and 48,000 hospitalizations every year. By 1981, measles incidence had fallen to less than 1% of pre-vaccine levels. Within the first 20 years of licensure, vaccination prevented an estimated 17,400 cases of intellectual disability caused by measles-related encephalitis. In 2000, measles was officially declared eliminated in the United States.

And yet, as of December 2025, the country is facing its largest measles resurgence since that elimination, with more than 1,900 reported cases. An estimated 92–97% of these cases have occurred in individuals who are unvaccinated or whose vaccination status is unknown, a sobering reminder that the victories of the past are not self-sustaining.

In 1921, the United States faced one of its deadliest infectious disease crises. Diphtheria, a vicious illness that causes severe respiratory distress and often leads to fatal heart and nerve damage, infected more than 206,000 people and claimed roughly 15,500 lives in a single year. It was a leading killer of children, and for many families, a diagnosis carried an almost certain sense of dread.

Hope arrived in 1923, when two independent researchers, Gaston Ramon and Alexander Thomas Glenny, developed the diphtheria toxoid, a technological breakthrough that transformed diphtheria from a common childhood killer into a rare, preventable disease. Before this advance, prevention depended on a toxin–antitoxin mixture (TAT), a crude and dangerous approach that required injecting live, active diphtheria toxin. While somewhat effective, TAT carried serious risks and could itself cause severe injury or death.

Ramon discovered that treating diphtheria toxin with formalin and heat neutralized its lethal effects while preserving its ability to stimulate protective immunity. He named this safer innovation “anatoxine.” In the process, Ramon made another critical observation: animals developed a stronger immune response when inflammation occurred at the injection site. This insight led to the discovery of adjuvants, substances added to vaccines to amplify the immune response. In 1926, Glenny further improved the vaccine by precipitating the toxoid with alum (aluminum salts), significantly increasing its effectiveness.

Throughout the 1920s, the United States deployed the new toxoid alongside older methods during large outbreaks, and by the 1930s it gradually replaced TAT entirely. The results were profound. As immunization efforts expanded, cases fell to approximately 19,000 by 1945, a reduction of more than 90% from the 1921 peak. In 1948, the diphtheria vaccine was combined into the DTP formulation. By 1980, only two cases of diphtheria were reported in the United States. Researchers estimate that since 1924, the U.S. vaccine program has prevented approximately 40 million cases.

Despite 155 nominations, Gaston Ramon never received the Nobel Prize. Yet his work, and that of his contemporaries, stands as one of the earliest and most consequential victories in the history of vaccination, a quiet triumph measured not in accolades, but in millions of lives spared.

Gaston Ramon also helped pave the way for the modern tetanus vaccine by applying the same toxin-inactivation process he had developed for diphtheria. Although the tetanus toxoid was licensed in 1924, it was not initially adopted for widespread civilian use. Its first true test came during World War II, when American soldiers were routinely vaccinated before deployment.

The results were extraordinary. By the end of the war, the U.S. Army reported just 12 cases of tetanus among millions of vaccinated troops, evidence of near-perfect efficacy against a disease once synonymous with battlefield death. Yet outside the military, tetanus remained a quiet but lethal threat. Between 1947 and 1948, the United States still recorded 500–600 cases annually. While this number may appear small compared to other infectious diseases, tetanus carried a fatality rate exceeding 90%, making infection essentially a death sentence.

The turning point came after the war, when tetanus vaccination was incorporated into the routine pediatric schedule as part of the combined DTP vaccine. Cases declined rapidly. By the mid-1970s, annual infections had fallen to roughly 50–100, a reduction of more than 80% from pre-routine vaccination levels. Since the 1940s, reported tetanus cases in the United States have declined by more than 99%.

The global impact has been even more profound. Between 1974 and 2024, tetanus vaccination is credited with saving an estimated 27.9 million lives worldwide, translating to approximately 1.4 billion years of life saved. It is a legacy measured not in headlines, but in the countless lives never lost to a disease that once killed swiftly, silently, and without mercy.

In the 1930s and 1940s, before widespread immunization, pertussis, better known as whooping cough, was a constant and deadly presence in American life. Each year, the United States recorded roughly 175,000–200,000 cases and approximately 9,000 deaths. Infants were especially vulnerable, many struggling to breathe through violent coughing fits that could last for weeks. For countless families, pertussis was not just an illness, but a prolonged and terrifying ordeal.

In 1932, two researchers at the Michigan Department of Health in Grand Rapids, Pearl Kendrick and Grace Eldering, began an ambitious side project after finishing their regular workdays. They traveled from house to house, visiting sick children and collecting bacterial samples using simple “cough plates.” Working with limited resources but extraordinary determination, they used this painstaking fieldwork to develop a safe, whole-cell killed pertussis vaccine. Between 1934 and 1935, they conducted the first large-scale controlled clinical trial for pertussis, an unprecedented achievement at the time.

The impact of their work soon extended far beyond Michigan. In 1940, the state began mass-producing and distributing the vaccine nationally. In 1944, their efforts were strengthened by African American chemist Loney Clinton Gordon, who tested thousands of pertussis cultures to identify a sufficiently virulent strain that would make the vaccine more potent. In 1948, the pertussis vaccine was combined with diphtheria and tetanus toxoids to form the DTP vaccine, simplifying delivery and expanding protection.

The results were dramatic. Within roughly 15 years of mass introduction, reported pertussis cases fell below 50,000 annually. By the end of the 1960s, cases had dropped below 10,000 per year. By 1976, the United States reported just 1,010 cases, a nearly 157-fold reduction from the pre-vaccine era. What had once been a routine childhood killer was reduced to a rare and preventable disease, not through chance, but through perseverance, public trust, and the quiet heroism of scientists who refused to accept suffering as inevitable.

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, Haemophilus influenzae type b, commonly known as Hib, was the leading cause of bacterial meningitis in young children in the United States. Each year, roughly 20,000 children were infected, and about 1,000 died. Among those who survived, permanent neurological damage was common: an estimated 15–30% were left with deafness, seizures, or lasting cognitive impairment. Before their fifth birthday, approximately one in every 200 children developed an invasive Hib infection. For parents, the disease was especially terrifying because it struck without warning, a child could wake up mildly ill and be critically sick within hours.

The bacterium itself was first described by Richard Pfeiffer during an influenza outbreak, leading him to mistakenly conclude it caused the flu, a misattribution that left it with its confusing name. In the 1930s, microbiologist Margaret Pittman made a crucial discovery: she identified “type b” as the specific strain responsible for nearly all invasive disease, including meningitis and bloodstream infections. This insight laid the scientific groundwork for prevention, though it would take decades to translate knowledge into protection.

The first effective Hib vaccine emerged through the independent yet collaborative efforts of two research teams. Dr. David Smith and Dr. Porter Anderson worked at Boston Children’s Hospital and later at the University of Rochester, while Dr. John Robbins and Dr. Rachel Schneerson conducted parallel work at the National Institutes of Health. Their path was long and uncertain, beginning in 1968 and stretching over 15 years. In one now-famous early experiment, Smith and Anderson volunteered as their own test subjects, injecting each other with an experimental vaccine to demonstrate that it could generate antibodies in humans.

In 1985, the FDA licensed the first pure polysaccharide Hib vaccine. While it proved effective in older children, it failed to protect infants under 18–24 months, the very group at greatest risk, because immature immune systems could not recognize the bacterium’s simple sugar coating. Confronted with this limitation, both research teams returned to the drawing board rather than accepting partial success.

By 1987, each team independently reached the same breakthrough: chemically bonding the weak polysaccharide to a carrier protein, such as a harmless diphtheria toxoid, enabled an infant’s immune system to recognize and respond to the bacteria. This innovation created the world’s first “conjugate” vaccine. Licensed in 1987 and approved for use in infants as young as two months old by 1990, its impact was immediate and profound. Reported cases fell by more than 99%, and by 1997, the United States recorded just 258 cases, down from 20,000 only a decade earlier.

For their role in virtually eliminating a leading cause of childhood meningitis, Drs. Smith, Anderson, Robbins, and Schneerson were awarded the Albert Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award in 1996. Their achievement stands as a testament to persistence, scientific rigor, and the extraordinary gains made possible when prevention is allowed to reach those who need it most.

In the 1960s, rubella was quietly devastating families across the United States. Often dismissed as a mild childhood illness, its true toll was revealed during the epidemic of 1964–1965. In just two years, rubella caused an estimated 12.5 million infections, 11,000 fetal deaths, and 2,100 neonatal deaths. Another 20,000 infants were born with Congenital Rubella Syndrome (CRS), suffering from blindness, deafness, heart defects, and lifelong disabilities. For many parents, the catastrophe unfolded slowly and cruelly, months after infection, when babies were born irreversibly harmed.

The scale of the tragedy spurred an urgent scientific response. In 1966, Dr. Harry Meyer and Dr. Paul Parkman at the National Institutes of Health announced the first experimental live-attenuated rubella vaccine, known as HPV-77. Alongside it, they developed the first reliable blood test to determine rubella immunity, allowing clinicians to identify those most at risk. Building on their work, Dr. Maurice Hilleman at Merck used a virus strain isolated by Meyer and Parkman to develop “Meruvax,” which became the first commercially licensed rubella vaccine in the United States in 1969.

At the same time, another breakthrough was taking shape. In 1964, Dr. Stanley Plotkin at the Wistar Institute developed the RA 27/3 strain of rubella virus. Although it would not be officially licensed until 1979, this strain ultimately proved superior, producing a stronger immune response with fewer side effects. In 1969, three rubella vaccines, Meruvax, Rubelogen, and Cendevax, were licensed for use in the United States, marking the beginning of nationwide prevention.

The impact was felt swiftly and it was measurable. Within seven years of the vaccine’s introduction, reported rubella cases fell by 78%, dropping from 57,686 in 1969 to 12,491 in 1976. In 1979, Plotkin’s RA 27/3 strain replaced all earlier versions in the United States and remains the standard today. Combined with Hilleman’s measles and mumps vaccines into the modern MMR, 97% effective against rubella, the disease steadily receded from American life.

In 2004, after 35 years of routine vaccination, endemic rubella was officially declared eliminated in the United States. What had once caused irreversible harm to tens of thousands of children was reduced to a historical memory, proof that when science, urgency, and public trust align, even silent epidemics can be stopped.

Prior to 1967, mumps was a near-universal childhood illness in the United States, causing roughly 186,000–200,000 cases each year. While often dismissed as routine, mumps was a leading cause of deafness and aseptic meningitis, an inflammation of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord. Early vaccine research began during World War II in an effort to prevent troop disruptions, but the first vaccine provided only short-term protection and was eventually abandoned.

The decisive breakthrough came two decades later, not in a planned trial, but in a quiet family moment. At 1:00 a.m. on March 21, 1963, Dr. Maurice Hilleman was awakened by his five-year-old daughter, Jeryl Lynn, who complained of a sore throat and a swollen jaw. Hilleman immediately recognized the signs of mumps. He drove to his laboratory at Merck & Co. to collect sampling equipment, returned home to swab her throat, and then went back to the lab to begin cultivating the virus.

Through repeated growth in hen’s eggs and chick embryo cells, a process known as attenuation, Hilleman weakened the virus until it could trigger immunity without causing full disease. In 1966, one of the first children to receive the experimental vaccine was his younger daughter, Kirsten, using the strain derived from her sister. The following year, in March 1967, Merck licensed the first effective live-attenuated mumps vaccine, Mumpsvax. That same “Jeryl Lynn” strain remains the standard used in the United States today.

In 1971, Hilleman combined the mumps vaccine with measles and rubella to create the MMR shot, a critical step for widespread adoption at a time when there was little commercial demand for a standalone mumps vaccine. In 1977, the CDC officially recommended mumps immunization for all children over 12 months of age.

The impact was profound. Within 15 years of licensure, reported mumps cases fell by 97%, dropping from 152,209 in 1968 to just 5,270 in 1982. After a brief resurgence in the mid-1980s among older children, a two-dose MMR recommendation was implemented in 1989. This adjustment led to further sustained decline, reaching an all-time low of only 231 reported cases in 2003, a 99.9% reduction from pre-vaccine levels. All of this began because a worried father answered his daughter’s cry at one o’clock in the morning, and chose to act.

Prior to 1991, before the CDC adopted a universal vaccination strategy, hepatitis B (HBV) represented a quiet but devastating public health crisis in the United States. Each year, an estimated 200,000–300,000 Americans were newly infected. Among them were 18,000–20,000 children under the age of ten, including roughly 9,000 infants infected at birth. At the same time, between 1 and 1.25 million Americans were living with chronic, lifelong HBV infections, many unaware they were contagious or that irreversible damage was already underway.

HBV is especially dangerous in children because their immune systems often cannot clear the virus. The risk of chronic infection is inversely related to age: approximately 90% of infants infected at birth develop lifelong infection; 25–50% of children infected between ages one and five become chronically infected; and only 5–10% of adults do. The consequences are severe. Roughly one in four children with chronic HBV will die prematurely from liver-related complications. Chronic infection causes progressive scarring of the liver, leading to cirrhosis, liver failure, and cancer. Globally, HBV is the leading cause of liver cancer.

The virus itself was discovered in 1965 by Dr. Baruch Blumberg, a breakthrough that earned him the Nobel Prize in 1976. Blumberg, working with Dr. Irving Millman, developed the first hepatitis B vaccine in 1969. Commercial refinement followed under Dr. Maurice Hilleman, who improved the vaccine at Merck in 1981. Although effective, early adoption was slowed by unfounded fears that the plasma-derived vaccine could transmit HIV, despite extensive evidence to the contrary.

To address both safety concerns and supply limitations, Hilleman collaborated with Chiron Corporation in 1986 to create a fully synthetic version of the vaccine. By inserting the viral gene into baker’s yeast, scientists were able to produce the hepatitis B surface antigen without using human blood. This recombinant vaccine, Recombivax HB, was licensed in 1986, followed by Engerix-B in 1989. Both remain global standards today.

Despite the availability of a safe and effective vaccine, the CDC initially pursued a so-called “high-risk” vaccination strategy. It failed. Between 30–40% of people living with HBV had no identifiable risk factors. Many pregnant women were not screened, and an estimated 35–65% of infected mothers went undetected. Nearly half of infected children under age ten acquired the virus through household contact, as HBV can survive for up to seven days on common surfaces such as towels and toothbrushes.

Faced with this reality, the CDC adopted a universal hepatitis B vaccination recommendation for all infants in 1991. The results were unequivocal. Between 1991 and 2025, chronic HBV infections among children and adolescents declined by 99%, preventing an estimated 500,000 childhood infections and 90,100 childhood deaths. Since licensure, more than one billion people worldwide have received the hepatitis B vaccine. Public health experts estimate that it has added several months to average human life expectancy.

Hepatitis B vaccination is now widely recognized as the world’s first anti-cancer vaccine. By preventing infection with a virus responsible for at least 80% of liver cancers globally, it transformed a once-inevitable trajectory of chronic disease and premature death into one of the most profound successes in modern public health.

I’ve asked you to travel a long way through history, and I appreciate you staying with me. But understanding what is happening now requires remembering what it once cost us to survive.

None of these victories happened by accident. Polio did not disappear because the virus became kinder. Measles did not retreat because parents worried less. Diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, rubella, Hib, hepatitis B, they were not defeated by hope or prayer or time. They were beaten because scientists refused to stop asking questions, because physicians accepted responsibility beyond their clinics, because parents volunteered their children for trials that carried real fear, and because policymakers chose to act decisively in the face of uncertainty.

This was not blind faith in medicine. It was earned trust, forged in a world where the cost of inaction was visible in iron lungs, crowded wards, tiny coffins, and children who never learned to walk, hear, or see. When Jonas Salk announced his vaccine worked, church bells rang not because Americans believed science was infallible, but because they had lived long enough with its absence. When parents lined up their children for measles shots, they did so remembering encephalitis, blindness, and death. When lawmakers funded mass immunization, they were responding to a public that demanded protection, not permission.

The reductions in disease we now take for granted were built by people who understood that prevention is a collective act. A vaccine in a vial does nothing on its own. It must be manufactured, regulated, distributed, trusted, and used, millions of times, quietly, year after year. Elimination was not a single scientific triumph. It was a social contract. And that contract is now fraying.

Vaccine distrust is not new. Fear has always followed medicine. What is new is the distance between memory and consequence. Today, most parents have never seen measles encephalitis, never watched a child suffocate from diphtheria, never heard the whoop of pertussis turn blue-lipped and silent. The very success of vaccination erased the evidence of what it prevents. And into that absence has rushed misinformation, amplified not from the margins, but from positions of authority.

Measles, declared eliminated in the United States in 2000, is back. In 2024 and 2025, more than 1,900 cases spread across the country, overwhelmingly among the unvaccinated. Children have been hospitalized. Children have died. The tools to stop this exist. What is missing is not science, but resolve.

This erosion of trust did not happen in a vacuum. Skepticism toward pharmaceutical companies is understandable in a nation scarred by the opioid crisis and corporate deception. But that justified anger has been misdirected, weaponized against vaccines by figures like Robert F. Kennedy Jr. who trade on distrust without bearing responsibility for the consequences. A single fraudulent study claiming a link between vaccines and autism, long retracted and discredited, has been allowed to outweigh decades of evidence and millions of lives saved. Policy decisions that once protected the most vulnerable are now being questioned, weakened, or abandoned in the name of ideology.

The scientists who built these vaccines did not work for applause. Gaston Ramon never received a Nobel Prize. Pearl Kendrick and Grace Eldering worked nights and weekends. Maurice Hilleman swabbed his own child’s throat at one in the morning because he could not accept another generation lost to chance. Their legacy is not recognition, it is absence. Empty hospital beds. Diseases children no longer know by name.

My niece has autism. I cannot speak as a parent, but I know this: even if the claims the administration is now touting were true, even if they were not, I would choose autism every single time if it meant she would live. If it meant she would grow, love, struggle, and shape the world in her own way.

We once understood what was at stake. We once chose science not because it was perfect, but because it was better than watching our children die. We chose it together, scientists, citizens, and leaders, bound by the belief that prevention is an act of care owed to those who cannot yet choose for themselves.

We once chose life.

We must choose it again.

Thank you, Mary, for this incisive post on vaccines, what they accomplish, and what life is like without them. I am old enough to remember fear about polio and my parents made sure to do everything they could to keep me from being exposed and I got the vaccine as soon as it was available. I did have the measles and spent a week in a darkened room. Once I was having an argument about the measles vaccine with my then LMT. He wanted to know if I would vaccinate them if I had children and I said absolutely. There was a pause and then he said thank god for the polio vaccine, but somehow did not make the connection. During the pandemic I got into an argument about the COVID vaccine with an ex-student who claimed she was a Christian. I wanted to know how one could be a Christian and still not want to keep people safe from COVID especially those who for some reason could not get the vaccine. I ended up blocking her.

This column should be mandatory reading for the people who say 'why go to the trouble and/or risk of vaccinating for a bunch of diseases I've never heard of.'

Those people could be enlightened by walking through a cemetery of graves from the 1920s or even 1950s and looking at all the children there.