The Fire Takes the House. The Design Takes the Future.

What no one tells you about the days after you lose everything

Yesterday I told a story about displacement. Today I’m telling the story of what comes after, when the fire is out, the sirens fade, and the machine begins its quiet work. The first thing you notice is how quiet catastrophe is after it’s done being loud. Fire is noise when it arrives, sirens and wind and the ugly roar of something eating the world the way hunger eats a body. It is noise when it moves, helicopters, shouted directions, the thump of adrenaline in your ears as you throw things into a bag without thinking about what you’re leaving behind. It is noise when it chases you, alerts buzzing, your neighbor’s voice cracking, the dog’s nails scrabbling on tile because it can smell what you can’t yet see.

But after, there’s a different silence. The silence of a neighborhood that used to have evenings, of a street where birds have forgotten which trees are still trees. The silence of your own house as a memory, the way your mind keeps walking through it even when your feet can’t. And then, in that silence, comes the envelope. It’s small, polite. It arrives like mail always arrives, like the universe hasn’t just rearranged your life into ash. It sits on the motel bedspread or the borrowed kitchen counter or the passenger seat of the car you’re living out of now. It looks like paperwork. It looks manageable.

Inside: numbers. But not the kind that tell a story, the kind that end one. A total, a deductible, depreciation on the roof you no longer have. A phrase like “actual cash value” that sounds reasonable until you realize what it means: “we will pay you for what your home was worth yesterday, not what it costs to rebuild tomorrow.” Not replacement, not return, just a math problem in place of a door. And if you listen closely, you can hear what the envelope is really saying, not in words, insurance is too careful for that, but in the arithmetic it uses to measure your grief: You can’t go home.

There are many ways we lose our homes in America. We lose them to layoffs and landlords, to illness and divorce, to “renovations” that are really evictions. We lose them to predatory lending and development schemes. But there is a newer way spreading across the map like a bruise across pale skin:

we lose them to climate disaster that arrives in one day and is finalized by paperwork over months. The fire is the headline, the insurance is the machine.

And machines are harder to mourn because they don’t look like villains. They look like policies and risk models and actuarial tables, something happening in an office far away from the smoke. But the distance doesn’t make it gentle, the machine can still break your heart with neutral language and reasonable deadlines. It’s displacement with a return address.

Why this matters

When insurance becomes unaffordable or unavailable, staying becomes a luxury item.

Disasters don’t just destroy buildings; they reorganize who gets to live where.

The people with the least margin, renters, fixed-income homeowners, low-wage workers, are hit first and hardest.

The “rebuild” becomes a sorting process: who returns, who scatters, who disappears into the statistical background.

There’s a myth that disasters are equalizers. We like the story where flames don’t care what you earn, where wind doesn’t check your credit score. But disaster has always had a favorite target: the people with the least margin. Because the fire is only the first wave, the second wave has forms. It looks like a family trying to remember everything they owned because someone will ask them to list it. Toothbrushes, winter coats, phone chargers, the pan you always used for Sunday breakfast. It feels like a test, prove you deserved what you had. Then the insurance process begins the way bureaucratic suffering begins: promises, deadlines, and hold music.

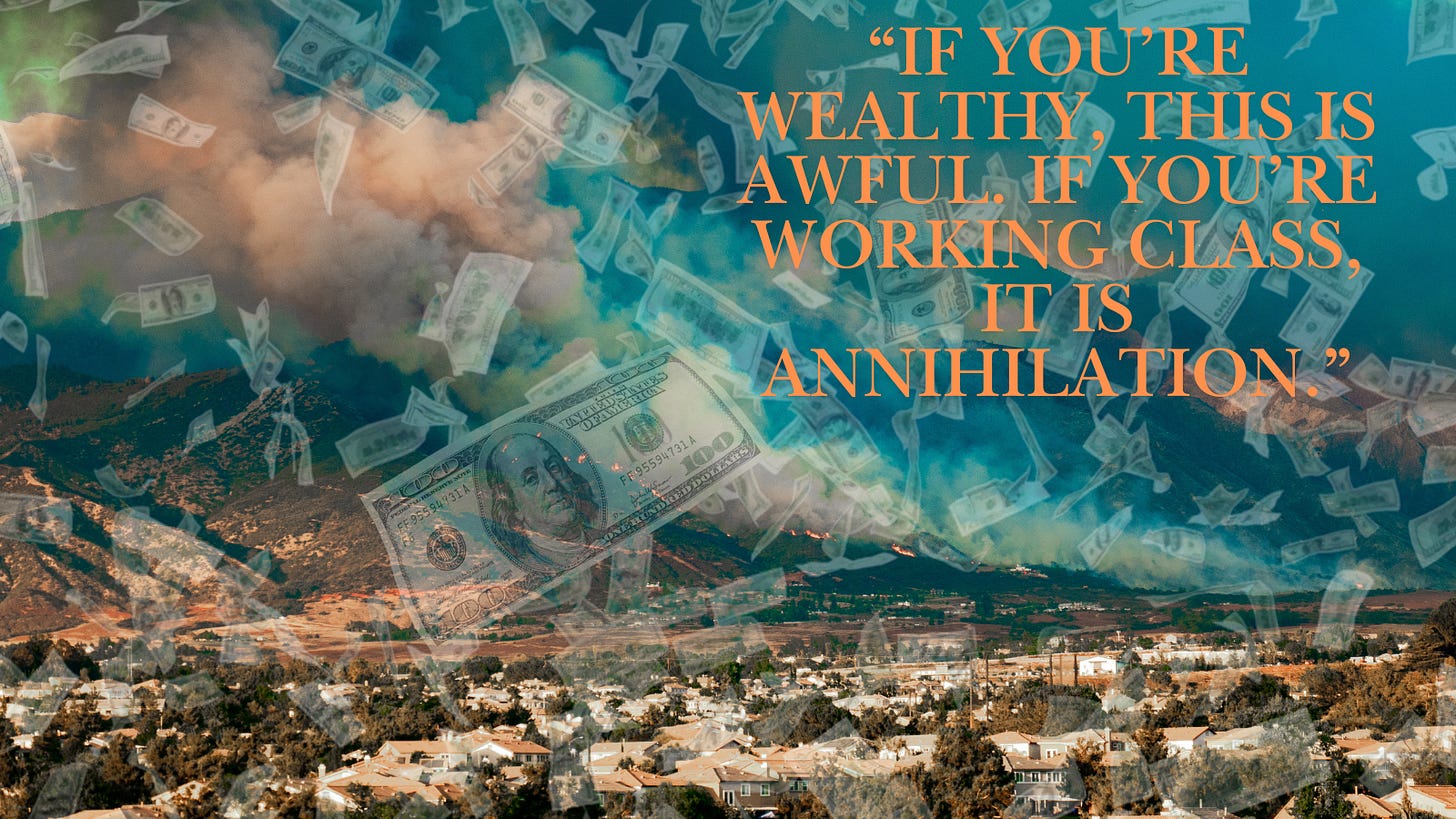

Document everything, wait for inspections and estimates. Get checks in pieces, dispute a line item and enter appeal. Miss a deadline you didn’t understand and watch the clock become a weapon. Sometimes the adjuster is kind, on the surface, and makes you feel like everything will be okay. Often, the adjuster changes midstream, because the company is using a rotating cast of contractors to handle volume. Each new voice asks you to retell the story, needs the documents again, and introduces a delay you didn’t know you were allowed to suffer. If you’re wealthy, this is awful. If you’re working class, it is annihilation.

Because wealth buys you time and expertise, lawyers, public adjusters, the ability to front costs while you wait. Most people don’t have that. They have a paycheck, gig work, a fixed income already stretched thin. They have kids, aging parents, disabilities. Lives that were finely balanced even before the smoke arrived. In that context, “delay” is not an inconvenience, it’s the end. Insurance doesn’t have to say no to push you out. It can say: not yet.

“Not yet,” while you pay for a motel because there are no rentals nearby. “Not yet,” while rebuilding costs climb and contractors are booked out for months. “Not yet,” while your mortgage still charges you for a house that no longer exists. “Not yet” becomes a slow eviction.

We like villains we can see. A wall of flame is honest, it tells you it is hungry, it doesn’t pretend to be on your side. But the letterhead pretends. Insurance is supposed to be the promise you buy against the worst day of your life. You pay month after month for the faith that when disaster comes you will not be alone, a kind of collective care. That’s the story, anyway.

So, what happens when the pool decides you are too risky to keep? The industry has a word for it: “exposure” Your roof is an “exposure,” your tree line is an “exposure,” your zip code is an “exposure.” In some states, even your credit score can be treated as one. Which is just a nice wrapper on a box with “higher premiums” stuffed inside. And that is exactly what is happening: people are being left out in the open. Because climate change is not just raising temperatures, it is raising the price of belonging.

There is a moment after a fire when you drive back toward your old neighborhood and realize you are crossing an invisible border. On one side is the life you had, on the other side is the life you can afford. The border isn’t marked by a sign, it’s marked by premiums. A renewal notice arrives with a number so high it might as well be a joke. A policy is “non-renewed” because the company is “reducing risk in the area.” The only available coverage costs more and covers less. And you start to understand the new geography of America: not red and blue, not rural and urban, but insurable and uninsurable.

Here’s the part that should make us weep: the uninsurable places are often the places people love most. Not abstract “high-risk zones,” but porches and childhoods and family gardens. When the insurance market retreats, it doesn’t just retreat from property, it retreats from memory. And the retreat isn’t gentle. Premiums rise, coverage narrows. People who can afford it adjust, people who can’t are forced into impossible choices: pay the premium or pay the medical bill; rebuild or start over somewhere you’ve never wanted to live.

We tell ourselves that moving is freedom. But most of us know the truth: moving is expensive, destabilizing, and deeply sad. Moving is trading community for survival. And the worst part is how quickly the displacement becomes invisible. First, you’re on a friend’s couch, then a motel. Then you’re in a rental an hour away, your kids are in a new school, your mailing address changes, your neighbors stop expecting you back. Until one day you realize you have become a story people tell in the past tense. “We used to know a family who lived up there.”

In the vacuum left behind, disaster becomes a lever for reordering the map by class. Until the place you called home becomes something unrecognizable. Sometimes it’s newcomers with money who can pay for hardening and expensive coverage, turning your vegetable garden into a hot girl sauna. Sometimes it’s investors, buying up the land for parking lots and retail shops. And sometimes it’s just absence, ruins that linger like a warning.

This is what the “uninsurable future” really means. Climate change isn’t only a scientific problem, but a moral one. We are building a country where safety is something you can buy and loss is something you can be priced into. And we are doing it with paperwork. A person who loses a home in a fire loses more than walls. They lose the small choreography of a life: the squeak in the third stair, the drawer that never quite closed right, the evidence of themselves, photographs, kids’ drawings, the marks on the wall where you measured their height.

Insurance cannot replace that. But it is supposed to do the next best thing: keep you from losing everything else, too, from being uprooted. Keep your community intact. When that fails, the loss multiplies. And the multiplying loss is the part we should not be able to witness without crying, because it’s not only the devastation that breaks you. It’s the way the system asks you to be reasonable about it. Be patient. Fill out the forms. Submit the receipts. Wait for the inspection, the estimate, the approval. Wait for the next check, the appeal, the next adjuster. Just: “wait.” Meanwhile, the calendar keeps moving, seasons change, and the news cycle moves on. But your grief remains, only now, it has a due date attached.

There is something especially cruel about the way our society treats climate disasters as individualized events. Your fire, your flood, your hurricane, your bad luck. Your responsibility to recover, as if it isn’t all of us, as if the smoke doesn’t travel.

We love to blame people for living where they live. But that is a system functioning exactly as it was designed. They live there because they were born there, because their grandparents are buried there, because their work is there, because the only home they could afford came bundled with risk. People live in “risk zones” because our housing market has turned “affordable” into a synonym for “precarious.”

And now insurance is becoming the mechanism that makes that precarity permanent. We should say it plainly: if a home cannot be insured at a price ordinary people can pay, it is not truly a home, it is a gamble. And if whole regions become uninsurable, then we are not dealing with isolated tragedies, but a structural eviction. The uninsurable future is a future where climate change acts like a landlord, not because of the disaster, but because of the profit potential.

So, what do we do with that knowledge? First, we stop calling it inevitable. We stop treating this as a natural outcome, as if there is no human hand on the dial. Insurance is regulated, housing is legislated, land use is decided. Infrastructure is funded, or not, by choice. We have built systems that allow profit to be extracted from risk without requiring those profits to be used to reduce that risk.

Second, we tell the truth about what “resilience” means. Resilience is beautiful when it describes a community holding each other up, it is ugly when it is used to romanticize suffering. Resilience cannot mean: “endure quietly, move away, let only the rich return.” Real resilience would mean that when a community is hit, the community is not scattered. That renters are protected, not forgotten. That rebuilding does not become a class filter. That we treat housing as shelter, as a basic right, not as a class privilege.

Third, we refuse to let the human stories be swallowed by the machine. Because the machine depends on our numbness. It depends on us accepting that a letter is just a letter, that a claim is just a claim, that a premium increase is just “the market.” But behind every number is a person, behind every “non-renewal” is a family packing boxes, behind every “exclusion” is someone realizing too late that the promise they bought was written in disappearing ink. If we cannot look at that and cry, we have lost something essential. And maybe crying is not the end of the story, but the beginning.

Grief is recognition. It says: “this mattered, these people matter, this place mattered.” And in this case it says: “this loss is not acceptable.” So, let the wedge go in, let it split you open, let it make you refuse the lie that “this is just how things are.” Because if we can still feel the heartbreak of it, then we can still choose differently. And we must, before the next envelope arrives, before the next quiet catastrophe, before the country becomes a map of places where only the wealthy are allowed to stay, and everyone else learns what it means to be “exposed.”

I feel for what you are going through and what you are writing about. I am apparently dense, however, in that I do not undersatand what you propose about doing to rectify any of the abuses you are recognizing. Can you give some concrete examples of what can be done by the rest of us to help the situation you are going through and those in the other circumstances you describe as well?

Heartbreaking posts this week, Shanley. Can I offer you a big hug? I've learned a lot and my empathy circle has been greatly expanded.