Laws of Armed Content

The Caribbean kill shot, Article II cosplay, and a presidency built on B-roll

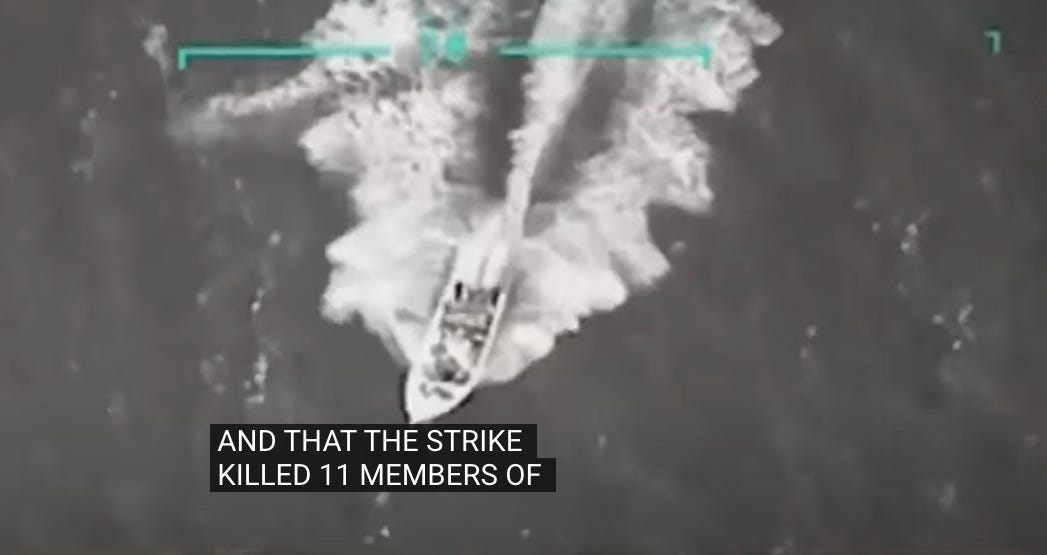

They blew up a boat and called it justice. Eleven people vanished beneath Caribbean water, and the Trump administration’s only burden of proof was a label: “terrorists.” Not identified by name, not caught with contraband, not even apprehended like ordinary suspects, just vaporized and retrofitted with a storyline later. The Pentagon got its clip, the White House got its Chyron, and we got yet another grim reminder that if you shout “narco-terrorist” loudly enough, the law becomes a fog machine.

Let’s start with the civics lesson this regime prefers you never take. Congress, not the president, declares war. When a president wants to swing a hammer outside a declared war, administrations traditionally rummage through the cupboard for a legal fig leaf: maybe the 2001 AUMF that was written to target the perpetrators of 9/11 and their associated forces; maybe Article II’s narrow authority to repel sudden attacks; maybe the UN Charter’s self-defense carve-out if an attack is imminent and there’s no time for the grown-ups to meet. What you don’t get is a blank check to treat a suspected smuggling skiff in international waters like a hostile gunboat headed for Pearl Harbor.

Here, the timeline reads like a parody. First came the explosion. Then came the legal theory. The public “justification” wobbled from “headed to the U.S.” to “headed somewhere else first” to “eventually the U.S., probably,” a Mad Libs of geography and intent. The video showed a blast, not identities, not cargo, not shots fired at U.S. forces. Senators Tim Kaine and Jack Reed asked the most basic questions, who were they, where’s the evidence, what law applies?, and got back slogans about “evil narco-terrorists.” Rand Paul, who usually saves his constitutional purism for mask mandates, suddenly remembered due process: if a drug boat really exists, you interdict it; you don’t execute the occupants at sea and workshop the rationale afterward.

Venezuela, for its part, flatly denies the U.S. version. Interior minister Diosdado Cabello went on state television to say their own investigation found the dead were not members of Tren de Aragua, not narco-terrorists, not traffickers at all. “How did they identify them?” he mocked. “Did they have a chip, a QR code you could scan from a jet in the dark?” To Caracas, the attack wasn’t interdiction it was murder dressed up as counter-terrorism.

International law isn’t much kinder to this stunt. The UN Charter forbids force except in self-defense, which requires necessity and proportionality. Necessity means there’s no alternative to force; proportion means the force fits the threat. The U.S. has boarded and seized suspected drug vessels for decades with the Coast Guard and Navy, meaning alternatives were not just available, they were standard operating procedure. And proportion? Missiles versus a runabout that, by the administration’s own shifting account, wasn’t attacking the United States, wasn’t an imminent threat, and might not have been bound for U.S. shores at all. If your legal defense is “drugs are bad in the abstract,” you’re not in self-defense territory; you’re in press-release territory.

Ah, but the magic parchment: the 2001 AUMF. Twenty-four years after 9/11, every president’s favorite Swiss Army knife. It targets those responsible for the attacks and their associated forces. It does not deputize the Pentagon to hunt “criminal suspects we don’t want to apprehend” anywhere on the planet. A Venezuelan gang in 2025 is not an associated force of al-Qaeda or the Taliban, however many times a press secretary says “terrorist” into a microphone. Pretending otherwise is how empires turn exceptions into default settings.

The domestic law problems multiply. The War Powers Resolution clock is now ticking because the White House filed the requisite letter, one that leaned on broad Article II language and conspicuously soft pedaled specifics about who, exactly, was targeted and why. And while the Supreme Court’s disastrous immunity ruling might insulate the president for “official acts,” it does not shield the rest of the chain of command. The U.S. War Crimes Act makes murder of non-combatants a federal crime; decades of executive-branch lawyering carve out a “public authority” exception only when the target is a lawful military target under the laws of war. A nameless, unidentified boat of alleged smugglers in peacetime, outside any active theater, is not that.

Even the rhetoric gives the game away. “Those days are over,” one senior official crowed, meaning interdictions in favor of annihilations. Translation: the old, legal, boring way, board, seize, arrest, doesn’t generate the tape you can pin to the top of your feed. What does? A grainy strike video and a “no safe harbor” tagline. It’s not counter-narcotics; it’s counter-programming. And look at the programming schedule. The moment the Epstein Files refuse to exit stage left, we’re treated to a blockbuster trailer: F-35s to Puerto Rico, eight warships and a submarine, Venezuela pounding the lectern about “battlefronts,” cameras panning to flight lines and stern faces. If you can’t bury the story that threatens you, drown it in jet noise.

None of this is to saint Venezuela’s kleptocracy. But sovereignty doesn’t evaporate because Washington needs a show. If “unwilling or unable” becomes an all-purpose wand, every powerful state gets to declare every weaker neighbor uncooperative and launch missiles on suspicion. That’s not a rules-based order; that’s a Yelp for airstrikes.

And so we return to the most galling, simple point: even if every person on that boat were guilty of the worst non-capital drug offenses imaginable, we do not summarily execute suspects. We stop the boat, seize the cargo, and try the case. The government has not named the dead, has not presented evidence of the drugs, has not proven destination or intent, has not even kept its own story straight. It has, however, produced an excellent distraction reel.

This is what happens when politics becomes a content farm with aircraft carriers. The rule of law is a prop, and human beings are extras. Any time the plot threatens to turn back toward the files they fear, they cue the next explosion and call it courage.

If Congress thinks letting Trump &Co. run amok keeps them their jobs, they are sadly mistaken. We can’t do anything about the Supreme Court except demand term limits, but we can do something about Congress.

The lack of outrage by elected lawmakers in Washington, DC boggles my mind. Trump has been wound up and just keeps going and going much like an Ever Ready battery . As the saying goes, "The chickens are coming home to roost", but sadly, they don't. We are facing invasion of cities, military control, lack of elections, and incompetence of the highest order in the White House and Halls of Congress, as well as in SCOTUS, FBI, and ICE and still the insults continue to pour from the mouth of he who would call himself, President. I call him and his lawlessness pure insanity.