How a Bonobo Taught Me to Build a Bridge out of Imaginary Grapes

What a bonobo’s make-believe reveals about trust, truth, and being together

Kanzi didn’t need a teacup to be full for the moment to feel real. In a bare, brightly lit research room, hard surfaces, empty pitchers, plain cups, he tracked an invisible stream of “juice” as it moved from one cup to another. He followed a pretend grape that wasn’t there as it traveled from an empty container into a jar. And, in the sweetest twist, when given the choice between a cup that held actual juice and a cup that held only the idea of juice, he chose the real thing. Imagination, yes, but not confusion. A shared game, not a mistake.

There’s something quietly revolutionary about that. Not because it turns the world upside down, exactly. More because it nudges it back into alignment. It reminds us that some of the traits we’ve wrapped in a special, human-only ribbon, the private fireworks of inner life, the ability to play along, the willingness to step into a story together, may not be ours alone. And in a season when everything feels like it’s either breaking, burning, or being shouted about, the idea of a bonobo holding a pretend tea party with a human is absurd in the best way. It’s a small bridge, built out of nothing at all, and still sturdy enough to stand on.

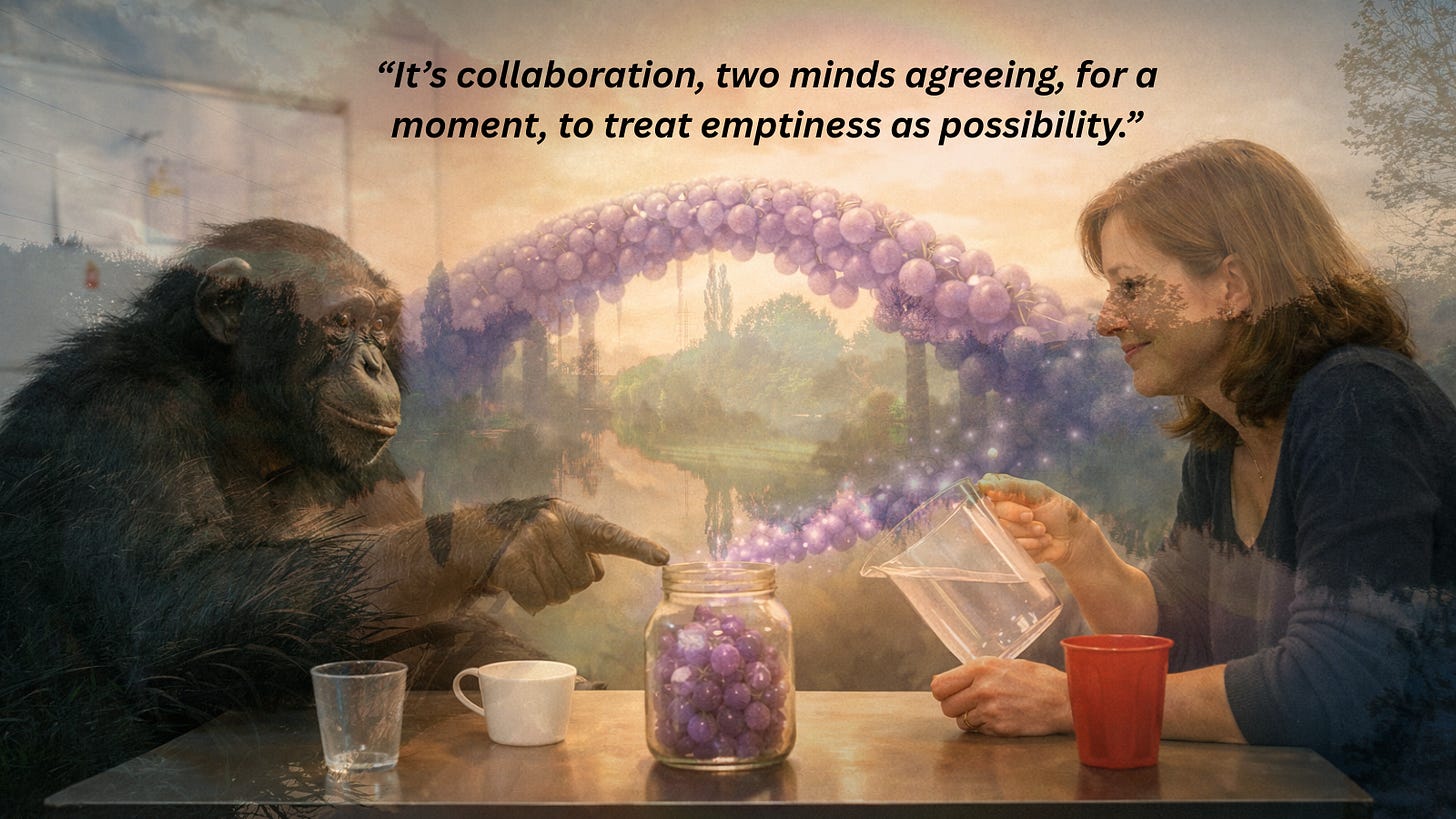

“Even in all the madness,” we say to each other, like a charm we rub between our fingers. Even in all the madness: a bonobo can pretend. I keep thinking about what pretending really is, when it isn’t a performance or a lie. Pretend is a kind of generosity. It’s the willingness to accept the invisible as temporarily meaningful. It’s collaboration, two minds agreeing, for a moment, to treat emptiness as possibility. When a child tips an empty teapot and announces “more, please,” they’re not confused about physics. They’re practicing how to be together. They’re learning that reality has layers, and that some of the most important ones are built with someone else.

We’re quick to associate imagination with escape, checking out, zoning out, hiding. But much of imagination is the opposite. It’s checking in. It’s the capacity to enter another’s frame and meet them there. Pretend play is less “look what I can do alone” and more “look what we can do together.”

That’s what makes Kanzi’s little acts of make-believe feel so bright: they suggest that this “we” instinct runs deeper than we like to admit. Not just in us, and not just as a metaphor. A bonobo across a table, watching a human pour nothing into something, and still tracking it, still holding the thread of the shared story, feels like proof that the world has more kinship in it than our news cycles allow.

And honestly, we need that right now. So much of modern life is an argument about what is real. Facts, fakes, spin, spectacle. We’re exhausted by it. Our guard is always up, because the cost of being fooled feels higher than ever. It’s no wonder we tighten our grip on certainty. No wonder we side-eye anything that looks like softness. No wonder we’re suspicious of wonder.

But pretending isn’t gullibility, it’s discernment plus trust. Kanzi’s preference for real juice matters here. If he were simply unable to tell the difference between the imagined and the tangible, the story would be less interesting and more sad. Instead, the research described him as capable of holding two categories at once: “real” and “let’s pretend.” He could inhabit an invented scenario while keeping his footing in the actual world. He could play without getting lost.

Isn’t that the skill we’re all trying to relearn? To live with imagination without drifting into delusion. To participate in stories without letting stories replace the ground under our feet. To make room for possibility while still caring about what’s true. There’s a grown-up version of pretend play that many of us do, and it’s so ordinary we forget it’s remarkable. When we laugh at a friend’s dramatic reenactment of something that happened at the grocery store, we’re agreeing to a shared exaggeration. When we read a novel and cry over a character who never existed, we’re consenting to be moved by invented pain. When we dress up for Halloween or toast at a wedding or whisper “good luck” to someone before a big meeting, we’re participating in rituals that depend on imagination, the belief that symbols matter because we agree they matter.

Society runs on a collective willingness to treat meaning as real. Money, marriage, laws, flags, even job titles. Even the idea of “the future” is a kind of communal pretend: a place we can’t see yet, that we plan for anyway. Sometimes that capacity gets weaponized, turned into propaganda or denial. But the root ability, the flexible mind that can juggle “is” and “as if,” isn’t the enemy. It’s one of our most vital tools, it’s what allows us to rehearse outcomes, simulate empathy, and practice being braver than we currently are.

And if a bonobo can do a version of that with us, maybe we’re not as isolated in our minds as we’ve told ourselves we are. There’s also grief tucked into this story, if you look closely. Kanzi has died. The experiments described in the article feel like a snapshot of a conversation that can’t continue. I find myself unexpectedly tender about that, about how much of scientific discovery depends on individual lives, each with their own quirks and capacities. One bonobo, described as extraordinary, a kind of “Einstein,” and suddenly we’re peering through a new window.

It makes the whole thing feel more personal. Not “apes can pretend” as a headline, but “this one being, in this one place, shared a small world with people for a while.” It’s an intimacy, it’s a reminder that knowledge doesn’t only come from numbers and charts; it also arrives through relationships, through patience, through sustained attention.

Imagine being the researcher across from him, trying to keep your face neutral, holding an empty pitcher over a cup, “pouring” nothing. Imagine the quiet tension of waiting: will he follow the invisible stream? Will he point? Will he play along? And then he does. Of course he does. Because he’s there with you, because he’s tracking your intention, not just your gesture. Because he understands that this moment isn’t about juice, it’s about the shared premise that “we are doing something together.” Even in a lab, it sounds like trust, and trust is a scarce resource these days.

We’re living through a stretch of history where many people feel like the social fabric is fraying: less shared reality, less shared decency, less shared patience. It can feel as if we’re becoming a species that can’t play together anymore. A species that has forgotten how to enter someone else’s frame without immediately trying to dominate it. Which is why this bonobo story feels like a tiny counterspell. Not because it solves anything, or because it suddenly makes the world safe or simple. But because it flashes a gentle truth: connection is older than our cynicism. The ability to meet another mind halfway, across a table, across a gap, across a difference in species, is not a modern invention. It’s ancient, it’s in the body, and it’s in the way attention can lean toward another and say, wordlessly, “Okay. I’m with you. What are we pretending today?”

That’s the feel-good part, the humility, the softening, the idea that the world is more crowded with inner lives than we account for. That we’re surrounded by beings who may have more going on inside than we can ever fully translate, and yet, somehow, we still find ways to overlap. A bonobo points to the cup with the imaginary juice, a human nods, and the pretend world holds.

There’s a lesson in that for the rest of us: we don’t need to agree on everything to share something. We don’t need perfect alignment to practice being together, we can start smaller. We can start with something as simple as attention, offered freely, we can start by acknowledging that someone else’s mind is real, even when we can’t see its contents.

And maybe, just maybe, that’s where the madness loosens its grip. Because when everything is loud and urgent and brittle, play is not frivolous. Play is resistance, play is rehearsal for hope. Play is a way of saying: the present is not the only story available. There are other scripts we can try, and other outcomes we can practice.

Somewhere, once, in a plain room with empty cups, a bonobo and a human made an invisible grape travel through space, and both of them agreed it mattered for long enough to be true. If that doesn’t make you smile, I don’t know what will.

Even in all the madness, the world keeps offering us these little proofs: that imagination is not just escape; it’s a bridge. And sometimes the strongest bridges are built out of nothing at all.

So well written, informative and inspiring!

I love you 💕