From Externalities to Enforcement, and the Story in which Harm Becomes “Necessary”

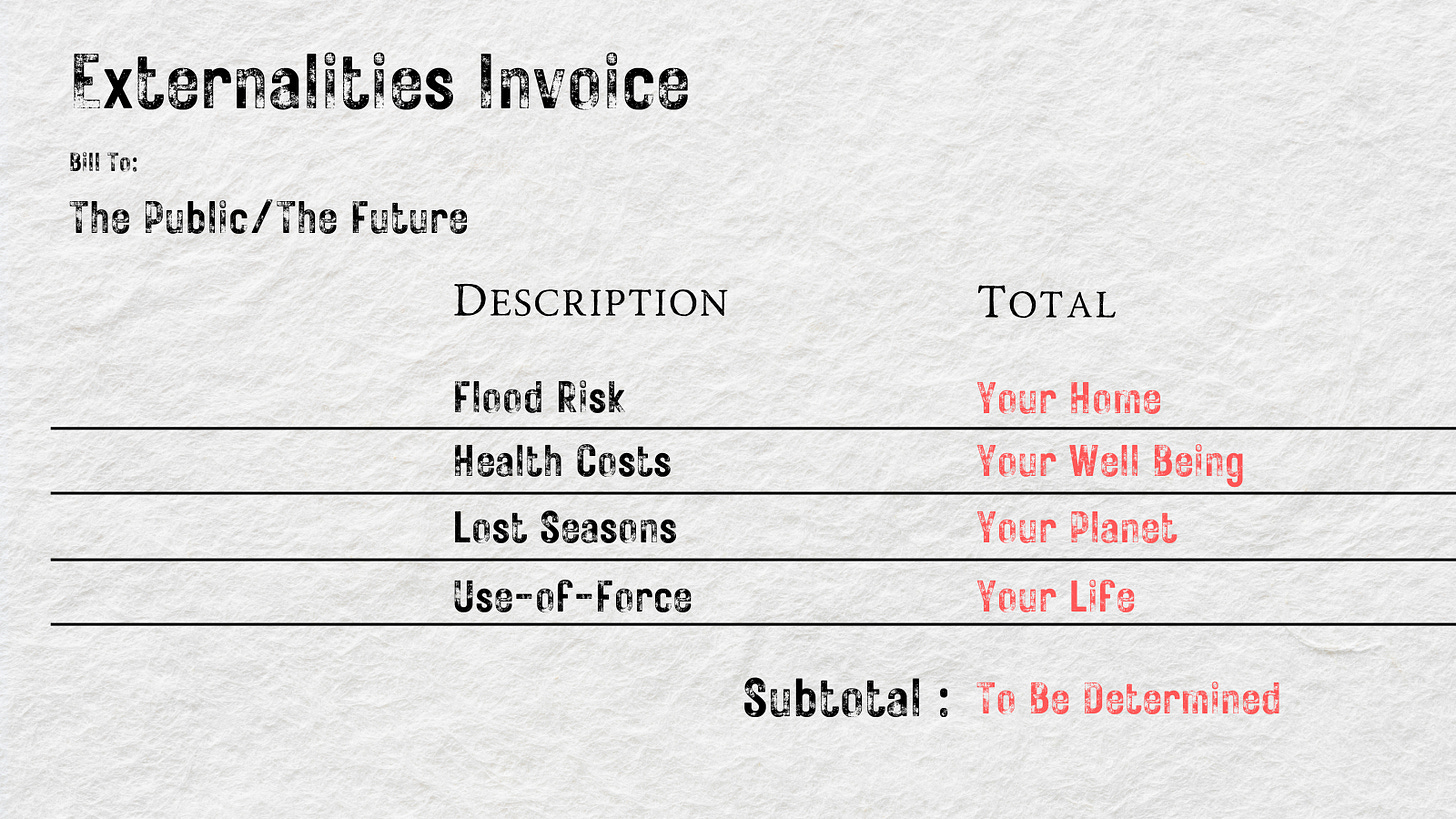

Profit externalizes. Power enforces. The public absorbs. How we were trained to live with damage we didn’t choose.

I keep thinking about how power looks when it stops asking permission and starts trying to explain away the consequences. Two systems make that shift feel normal. One is capitalism’s “polite” taking, profit separated from consequence, harm treated as someone else’s problem. The other is authoritarian taking, the shrinking of accountability until force and fiat can stand in for consent. On their own, each can do damage. When they braid together, they make the climate and the public easier to rob: one side supplies incentives to extract; the other supplies permission to ignore whoever gets hurt.

This week, the news has been full of scenes that feel less like “policy” and more like governance by force, a shooting in Minneapolis involving a federal immigration officer and taking the life of a mother of three; another shooting in Oregon, in East Portland, during a traffic stop involving a federal border agent; competing official narratives; and state authorities saying they’ve been blocked from the investigation. Reporting has also tracked a broader pattern of shootings and other use-of-force incidents connected to the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown; while noting how hard it is to get consistent, up-to-date federal use-of-force data at all. Whether you see these events as tragic exceptions or predictable outcomes, they share a message; someone is deciding what risks the public must live with and doing it from behind a wall of authority.

The point isn’t that climate change and street violence are the same. It’s that both reveal the same machinery: who gets to decide risk, who absorbs the fallout, and how hard it is to appeal the decision once it’s wrapped in legality or force. From violence you can see, to the theft that is drowned out, the bridge is procedure, how decisions become “just what had to happen,” and how quickly the people living with the consequences are told they’re not allowed to question it.

Climate change is often described as a technical problem, parts per million, megawatts, timelines. But at its core, it’s a form of stealing. Taking a stable atmosphere, taking livable seasons, taking the safety net of a predictable world, and sending the invoice to people who didn’t consent and can’t afford it. Capitalism doesn’t need a villain twirling a mustache. It only needs a system where profit can be separated from consequence. The clean term is externalities. The blunt term is dumping. Dumping pollution into air and water, dumping health costs onto communities, dumping risk onto the future. The industrial era normalized a bargain that still defines our economy, growth now, cleanup later but “later” keeps arriving with interest. Even when capitalism innovates, it often innovates in ways that preserve the right to dump, shifting responsibility from producers to consumers, or promising that someone else, somewhere else, will offset the harm.

Then comes the second move, when the people living near the damage begin to resist, the system learns to move the damage. Extraction goes outward. Supply chains stretch. Industries migrate toward weaker labor protections and weaker environmental enforcement. The point isn’t that trade is evil; it’s that the system is built to find the path of least resistance, and the path of least resistance is usually paved through communities with less power. Look long enough and you can’t miss the historical echo of empire, land reorganized for commodities, ecosystems converted into revenue, and local lives treated as collateral for distant prosperity. The climate crisis inherits that geography. We don’t just emit carbon; we export harm.

And then there’s capture, not always crude bribery, more often a soft, legal, respectable kind of influence that teaches governments to fear the wrong things. It’s the fear of disrupting markets, spooking investors, raising costs, angering donors, while treating ecological collapse as a “long-term,” problem, perpetually scheduled for the next administration. In that world, delay isn’t a failure; it’s a strategy. If profits are private and damages are socialized, postponing action is rational. And if you can turn climate policy into consumer lifestyle, recycling, personal virtue, green products, then you can keep the basic structure of extraction intact while selling the public a sense of participation.

Then there’s authoritarianism which doesn’t rely on externalizing costs; it relies on shrinking accountability. It does this by narrowing who counts as “the public,” and by treating scrutiny as sabotage. You can’t correct harm if people are afraid to report it, afraid to organize about it, afraid to sue about it, afraid to publish the data. Authoritarian habits turn politics into loyalty and dissent into threat. And because legitimacy becomes a performance, authoritarian systems often prize speed and spectacle; the show of force, or the triumph of will. Sometimes that speed can build useful infrastructure. But without durable consent and checks on abuse, it also builds sacrifice zones, places and people designated to absorb damage so the center can claim success.

This is where Trump enters not as a digression but as a live case study. His second-term project has openly framed itself as muscular executive action and rapid “reform.” In the immigration crackdown, we can see how quickly that posture becomes combustible: shootings on opposite sides of the country; with sharply competing accounts; and state officials lacking access. I’m not asking you to accept a single neat story about intention. I’m asking you to notice a pattern: when the state treats force as a routine delivery mechanism, violence stops being surprising and starts being a foreseeable cost of governance.

The climate link is procedural, not metaphorical. Climate protection in the United States often lives in boring architecture. Environmental review, public comment, disclosure, the slow grind that gives ordinary people a chance to interrupt decisions that would otherwise be made over their heads.

That is why fights over the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) matter. In February 2025, the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) published an interim final rule removing its NEPA implementing regulations from the Code of Federal Regulations, effectively stripping the government-wide baseline that standardized how agencies do environmental review. On January 7, 2026, the White House celebrated CEQ’s final administrative action reaffirming that move as “permitting reform,” and CEQ lists the final rule as dated January 8, 2026.

Whatever your view of how long permitting should take, this is the underlying political question: if process is one of the few levers the public has, then stripping process is a way of stripping power. Speed can be real progress, especially for clean energy, transmission, and resilience. But speed without enforceable transparency is not “efficiency”; it’s a transfer of decision-making away from the people who will live with the consequences. It is, in the language of this essay, another kind of theft: taking time, voice, and recourse from the communities most likely to be harmed.

If history tells us one thing, it’s when accountability weakens, force fills the gap. The broader violence story matters here because it shows what happens when institutions that should absorb conflict peacefully start to fail. DHS has warned in its threat assessment that lone offenders and small groups can act with little to no warning, and it flags heightened concern around sociopolitical developments, especially elections, as factors extremists may exploit. We don’t need to claim that one leader is the sole author of this era to see how leadership can amplify it. Narratives about stolen elections have repeatedly served as accelerants in the broader ecosystem of threats and violence. And the long shadow of January 6 remains part of our political weather, the House Select Committee’s final report documents the attack and the conditions around it, a reminder of how quickly the line between rhetoric, mobilization, and violence can erode.

When those conditions harden, when force becomes normal and accountability becomes optional, climate policy becomes easier to bend toward extraction, because the public’s ability to resist is treated as disorder. That is the tag-team; markets that reward taking, and governance that suppresses those who object to being taken from.

If this essay is going to earn its anger, it should end with demands that aren’t just vibes. “Stop stealing” has a policy translation. Firstly, publish the data. Use-of-force reporting that can’t be buried, investigations that can’t be walled off from legitimate oversight, disclosure that doesn’t depend on goodwill. Secondly, protect process. Public participation, environmental review, and legal recourse as rights, not obstacles to be “streamlined” out of existence. Finally, enforce floors. Standards with teeth so the atmosphere isn’t treated like an unowned dumping ground, and so “later” can’t keep arriving with interest.

It also means protecting the right to organize and protest, because climate action without civic power becomes another top-down program done to people instead of with them. And it means acknowledging that a just transition is not charity, it’s the price of legitimacy. If the public experiences decarbonization as yet another elite project that extracts from them, bringing higher costs, fewer choices, and no voice, then authoritarian politics will keep finding fuel.

The atmosphere doesn’t care whether emissions come from markets or ministries. But people should care when either one learns it can take without consent. The violence in the streets and the violence in the climate are not the same note, but they do rhyme. Both are what happens when power stops seeing the public as the source of authority and starts seeing the public as an obstacle. If we want a livable planet, we’ll need more than better technology. We’ll need to make stealing, of rights, of accountability, of the future, politically expensive again. I won’t sit here and type away without at least somewhat of a solution, so here goes. We must educate ourselves, as is becoming my favorite phrase, “clarity itself is an act of resistance.” With this education we must elect leaders that won’t stand for hidden reports or a lack of accountability. We mustn’t forget who we are fighting for, our children, our friends, our planet, our future. But most importantly, we can’t let the rhetoric make us believe we don’t matter, we must remember that without us they are nothing, and we have the power to take back control, one small act of resistance at a time.

Was the newly released video from the shooter’s body cam? Or from his hand-held mobile phone? That needs to be made clear, especially if it’s his cell phone. Holding on to the phone in one hand and the gun in the other and not dropping the phone in the critical moment of shooting…would say something about his intention and his lack of fear.

Excellent essay. Thank you. I am older with no direct descendants and I can see clearly where we are headed. One of the things that amazes me is the assumption that things are going to go along the same, that a sports schedule several years hence is actually going to happen for instance. It might, but we may be in utter chaos in a few years.