Dr. Oz Discovers Measles

A celebrity doctor tiptoes away from RFK Jr.’s vaccine fever dream, just in time to save his résumé, and maybe (tiny miracle) the rest of us.

On Sunday morning TV, Dr. Mehmet Oz did something that, by the standards of our current national health discourse, counts as a small civic miracle: he advised Americans to get vaccinated against measles. “Take the vaccine, please,” he said, as if he were pleading with a toddler to eat one bite of broccoli before the screen time kicks in. Which, in a way, he was.

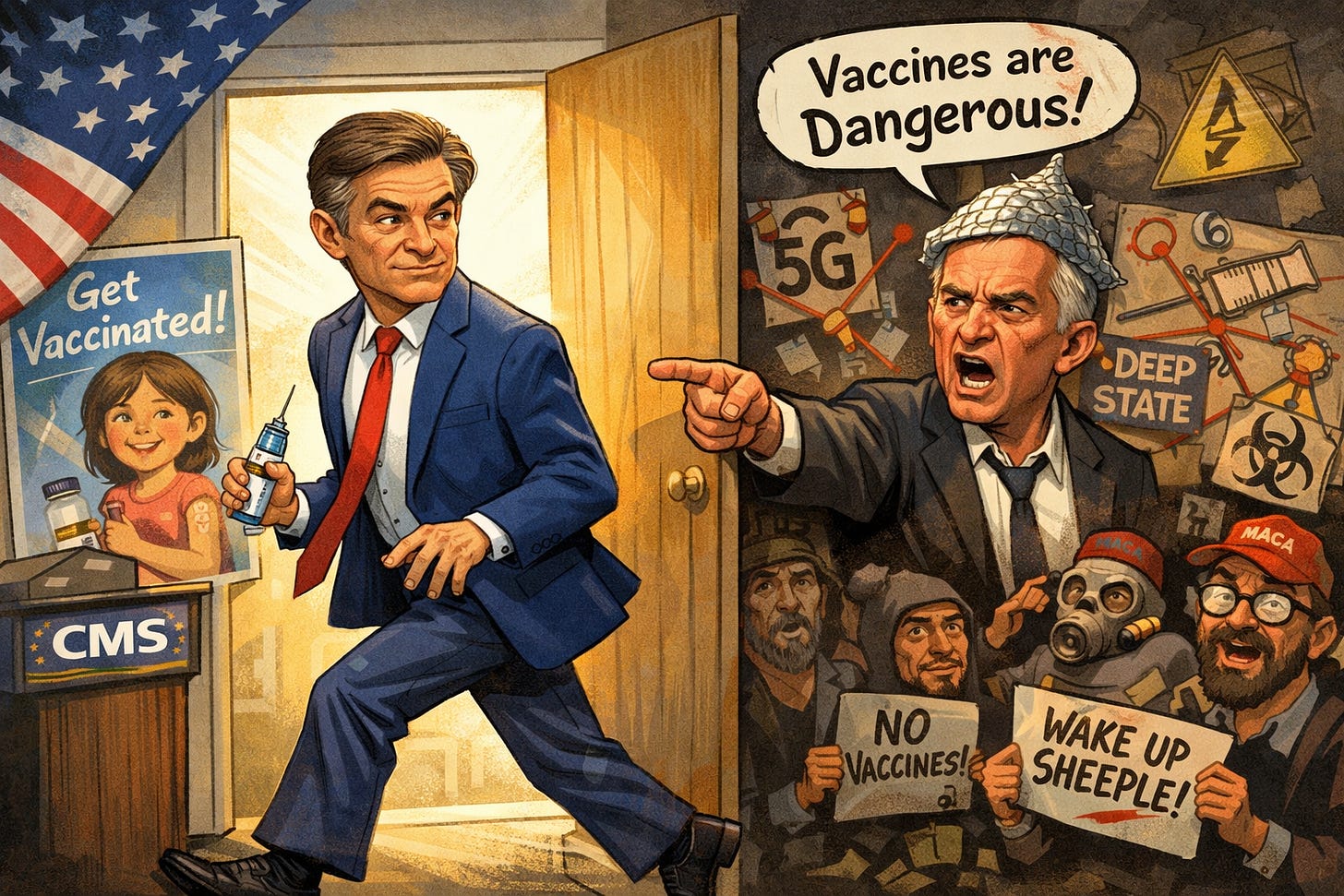

This is notable not because the sentence is controversial in medicine. It is not, it’s like a fire chief saying, “If your house is on fire, you should consider water.” It’s notable because Oz is not merely a guy with a stethoscope and a daytime-TV sheen anymore; he’s a senior federal health official inside an administration whose health secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., built an entire public persona around the vibe that vaccines are an ominous plot dreamed up by sinister pharmacists in windowless rooms.

So, when Oz says “vaccine,” what he’s really doing is saying something else too: distance. A faint, cautious, carefully measured distance, like a man inching away from the loud table at a wedding reception where the groomsman is explaining how the moon landing was staged by Big Thermostat.

And look, we should keep our expectations calibrated. This is not the moment when Dr. Oz rips off his lapel microphone, stands on a desk, and recites a stirring monologue about epidemiology, democracy, and the sanctity of peer review. This is not the “Et tu, Mehmet?” betrayal scene Kennedy’s critics have been waiting for. It’s more like Oz glancing at the exits, noticing the smoke, and remembering, belatedly, that he’d rather not be the guy on the news later insisting that fire is a personal choice.

But the smallness is part of the point. The story of our era is not usually dramatic ideological conversions. It’s the slow, reluctant emergence of self-preservation, people doing the right thing not because they love the right thing, but because they have finally realized the wrong thing is going to leave a stain that won’t come out in the wash.

Measles has that effect. Measles is what happens when the consequences stop being theoretical. It doesn’t politely restrict itself to op-eds and vibes. It spreads, it leaps across rooms, it finds the unvaccinated, and it turns a society’s abstract mistrust into a pediatric ward problem.

If you’ve been alive for the last decade of American politics, you can probably feel the familiar structure here. A movement rises on contrarian energy: the sense that elites are lying, experts are corrupt, the “truth” is what you can intuit from a podcast host’s facial expressions. Then reality shows up like an uninvited guest and starts overturning the furniture. Suddenly the people who built their careers selling skepticism have to decide whether they are going to live inside their own product.

Kennedy, famously, has made that choice before. In prior moments, he has treated vaccination as a personal preference and suggested alternative “treatments” that live in the shadowy realm between folklore and wishful thinking. That’s not just a policy stance; it’s an identity. It’s the sense that the entire apparatus of public health, its recommendations, its campaigns, its institutional voice, should be replaced with something more “open-minded,” which is a euphemism that in practice often means: more vulnerable to whatever rumor has the best lighting.

Oz, meanwhile, has always been a man of two worlds. He is trained as a physician. He is also trained, in the deepest way, as a performer. He knows how to deliver a message with just enough authority to sound like science and just enough ambiguity to keep the audience that wants magic from turning the channel. That combination is how he became Dr. Oz in the first place: a figure who could talk about medicine while flirting with the edges of the supplement aisle. But now his job is not to sell the feeling of health. His job is to help govern it.

And governance has a way of taking all your fun metaphors and setting them on fire. In the clinic, you can be charming. In the campaign, you can be contrarian. In a federal role during an outbreak, you eventually have to decide whether you are going to say the simple thing out loud: the vaccine works, please take it.

What we’re watching, potentially, is Oz discovering a basic truth about political alliances: they are delightful until they are not. They are a warm bath until suddenly they are a subpoena. They are a brand synergy until they are a headline that says, “Hundreds of cases,” and your name is printed next to the word silence. So yes, let’s entertain the uncharitable but extremely plausible reading: this is Oz slowly breaking with Kennedy to save his own reputation.

Not in a heroic, principle-driven way. Not the romantic version of dissent where a man risks everything for his conscience. More the pragmatic version where a man looks at a fast-approaching train and thinks, I should probably not be on the tracks when this hits. Because if you are Dr. Oz, trained physician, famous TV doctor, government appointee, you can survive many things. You can survive being mocked for miracle cures. You can survive being memed. You can survive being the punchline of late-night jokes. But you cannot survive being remembered as the adult in the room who had the microphone and chose to mumble while a preventable disease surged through schools.

That’s not just political damage. That’s professional disgrace, the kind that follows you into every future “biography” paragraph, forever prefaced by the phrase, “during the measles resurgence.”

Reputation, in other words, is a kind of vaccine too. It doesn’t stop you from getting sick, but it can stop you from dying socially when an outbreak of accountability goes airborne. And once you understand that, Oz’s plea makes perfect sense. He is not suddenly becoming a different person. He is becoming the person he needs to be to remain in the room.

Here’s where it gets almost funny, in the dark way American politics has become funny. We are so starved for sanity that an official saying “take the vaccine” feels like a bold moral stand. It is the lowest possible bar, and yet we experience it as a beam of light through clouds because the clouds have been so thick for so long. It’s like waking up after a long night and being moved to tears when someone offers you a glass of water. You didn’t know how dehydrated you were until you heard the words, “This will help.”

In a normal country, this wouldn’t be newsworthy. A health official would urge vaccination during an outbreak, the way meteorologists urge you not to drive into a hurricane. There would be public campaigns. There would be messaging. There would be coordination. There would be the basic machinery of state capacity humming in the background. Instead, we have a moment where the CMS administrator makes a plea on cable news, and everyone scrambles to interpret it like Kremlinology. Is he with him? Is he against him? Is this a sign of fracture?

That is how low our expectations have sunk: we are reading tea leaves in a cup of MMR. But maybe that’s also where the hope is hiding. Because fractures matter. They are how delusions lose their monopoly. Movements that thrive on shared unreality depend on constant reinforcement, everyone nodding along, everyone repeating the same talking points, everyone acting like the emperor’s new clothes are a visionary “MAHA” redesign of the textile industry.

The danger of a figure like Oz saying “take the vaccine” is not that it persuades the diehards. It probably won’t. The danger is that it makes the fence-sitters feel less alone. It gives cover to the people who privately know better but have been afraid to say so out loud. It signals, quietly, that it is possible to defect without immediately being cast into the wilderness.

If you want to understand how public crazes end, it is rarely because the craziest people suddenly wake up sane. It’s because the less-crazy people decide they’re done pretending. It’s because a few opportunists decide the upside has evaporated and the downside is now a permanent record. It’s because a coalition that was held together by vibes starts to be held together by liabilities, and liabilities are heavy.

Oz is not an avatar of moral clarity. He is, at best, an indicator species: the creature you watch to see what the environment is doing. When he starts insisting on vaccines, it’s not proof the era of vaccine skepticism is over. It’s proof that the costs are rising. The water temperature is changing. And that matters, because movements like Kennedy’s do not collapse under the weight of arguments. They collapse under the weight of consequences.

Measles is a consequence. It’s also an embarrassment. It’s a disease we had essentially pushed off the stage, the kind of thing Americans treat as a grim documentary segment about somewhere else. For it to return, and for officials to flirt with indecision, creates a uniquely potent kind of national shame, the sort that even cynical political actors can recognize as dangerous.

So perhaps Oz sees it. Perhaps he looks at the outbreak map, the child cases, the headlines, and he understands that there are only so many times you can wink at conspiracy-adjacent rhetoric before history files it under “complicit.” Or maybe he doesn’t “see it” in the moral sense at all. Maybe he just sees the brand risk.

Either way, here is the uplifting part, the small but real consolation prize of living through this circus: even self-interest can move the world in the right direction. Sometimes the only thing that makes a person stop enabling madness is the dawning realization that madness is not a costume you can take off at the end of the season. That it stains. That it lingers. That it will be quoted back to you at inconvenient moments.

And if we’re lucky, if the outbreak continues to force clarity, if the institutional pressure keeps building, if enough people decide they’d rather not be the villain in the footnote, then more of these figures will start doing what Oz did: saying the simple, sane thing into a microphone. “Take the vaccine, please.”

It shouldn’t feel like hope. It should feel like basic competence. But in 2026 America, basic competence is a radical act. And if even a few people who once flirted with the fringe start to inch back toward reality, not out of enlightenment, but out of fear of being remembered, then yes: maybe there is hope for us yet. Not because the system suddenly became wise. Because the system finally remembered it can’t out-spin a virus.

i was surprised and delighted when i saw that he said this. i am not sure of his motives, but will take the bold step regardless. he may have never bought into the whole Kennedy thing anyway, but wanted the gig after his failed senate campaign here in PA, or he may have an eye for history that the rest of these dopes do not seem to have... perhaps envisioning medical texts or history books prominently linking his name with unnecessary and avoidable illnesses and deaths. what will be interesting to watch is what happens inside maga world now.. is there so much other bad doodoo taking place that no one notices? will the Epstein files and the international spy ring screw ups with Cruella deVille eclipse this, or will people begin to question who they should be believing and will Oz get bounced out or sidelined? it is so so sad to see the number of cases skyrocket. so avoidable and each and every one is the responsibility of these clowns who have weaponized the health care system and destroyed the work of one of the best health research organizations in the world

He lost my respect way before he entered this administration. It seems too little too late, but I get you, it's something.