A Turtle Named Pyari

A story about rescue, release, and keeping your heart open

On a cold morning in Florida, cold by Floridian standards, which is to say everyone is dressed like they’re about to summit Everest, the Atlantic looks like a vast, indifferent sheet of steel. The ocean does not care about your deadlines, or your opinions. It does not care about the headlines, the hot takes, the thousand little alarms going off in your pocket. The ocean has been doing ocean things for a very long time, and it will keep doing them long after we’ve finished arguing about whose fault everything is.

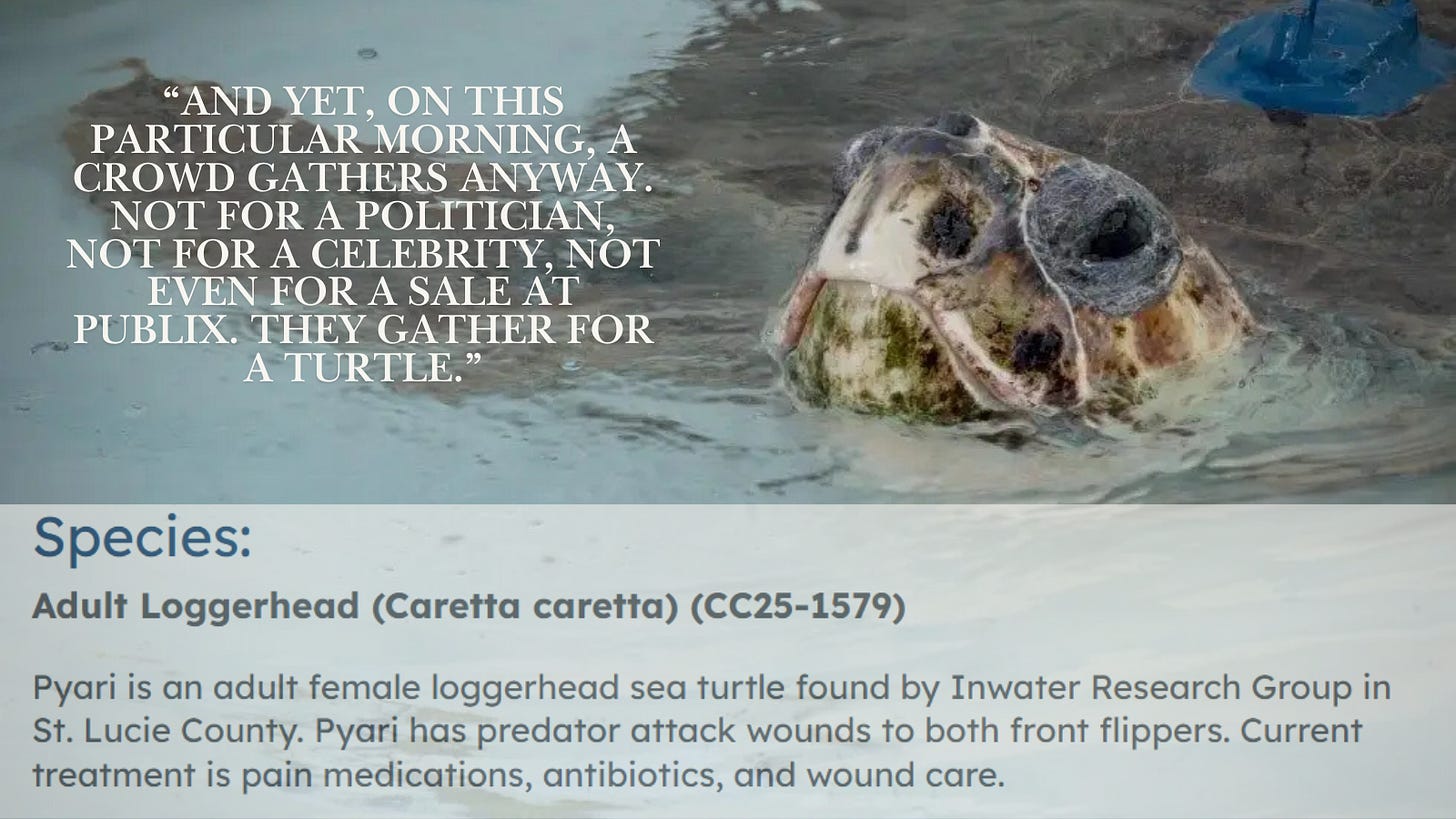

And yet, on this particular morning, a crowd gathers anyway. Not for a politician, not for a celebrity, not even for a sale at Publix. They gather for a turtle. Her name is Pyari, which means “beloved” or “lovely,” and if you’re the kind of person who rolls your eyes at the naming of rescued wildlife, “What’s next, a dolphin named Persephone?” I get it. Naming can feel like a sentimental shortcut, a way of smuggling emotion into a story that should be about science and ecosystems and hard numbers.

But here’s the thing: the people who named her are scientists, veterinarians, and rehab staff. The kind of professionals who spend their days looking at the unglamorous mechanics of survival: bone, blood, tissue, infection, temperature regulation, and hydration. They do not name animals because they can’t handle reality. They name them because they live in it. Because when you are sewing back together the torn edges of a creature that can’t thank you in any language you understand, you learn that sentiment is not the opposite of rigor. It’s the fuel.

Pyari came in badly injured, likely after a predator attack. She arrived with wounds to her neck and shell, and with damage to both front flippers, those elegant, powerful paddles that make a sea turtle look like it’s flying underwater. Months of care followed. Surgery. Monitoring. Healing. And then, the hardest kind of healing: acceptance. Her left forelimb couldn’t be saved. It had to be amputated. Three flippers. One ocean.

If you want to find the metaphor, it’s sitting right there, blinking slowly in the winter sun: a creature with less than she started with, heading back into a world that will not pause to make room for her. The sea does not install ramps. It does not soften its edges. It does not put up helpful signage that says, “Caution: currents.” But the people on the beach do something the ocean won’t. They adjust, they plan, they care, and they ask: what will it take for you to have a shot?

There’s a moment in stories like this when we’re supposed to clap, release day, the heroic return, the soft-focus triumph. And yes, the turtle crawls toward the water, and yes, the crowd cheers, and yes, it’s hard not to feel your throat tighten in that embarrassing way it does when you watch someone reunite with their dog at an airport.

But the part I can’t stop thinking about isn’t the applause. It’s the spreadsheet. Because Pyari doesn’t just get a send-off, she gets a satellite tag. A little antenna, bobbing above her shell like a tiny flag of intent: we are still paying attention. We are not only here for the satisfying ending, we want to know what happens next.

It’s easy to be compassionate in a moment that makes for a good photo. It’s harder to be compassionate in a way that requires follow-through, budgets, equipment, staff hours, data interpretation, and the unglamorous truth that you might never get the resolution you want. Satellite tags are expensive, around ten thousand dollars, and they don’t promise certainty. They don’t always transmit forever. Sometimes the signal disappears because the tag fails, or falls off, or the turtle swims into the kind of watery dead zone where the modern world’s little invisible nets can’t reach.

And sometimes… sometimes the signal disappears for the reason you don’t want to name, because naming it would puncture the story’s warm glow. The veterinarians and researchers know all of this, they know the ocean is not a Disney movie, they know survival is not guaranteed. And they do it anyway, there’s a kind of stubborn tenderness in that. We live in an era that sells cynicism like it’s wisdom. Scroll long enough and you start to feel like caring is naïve, that the only safe posture is irony, that the only sane response to a chaotic world is to keep your heart small and your expectations smaller. There is always more bad news than you can metabolize. There is always another disaster, another cruelty, another bureaucratic shrug. So, a turtle can feel almost absurd, in the great burning theater of modern life, what is one reptile with three flippers?

But that question is exactly the trap. It’s the arithmetic that slowly hollows out our humanity: if I can’t do everything, I’ll do nothing. If I can’t fix the world, I won’t fix the small corner in front of me. If I can’t guarantee an outcome, I won’t take the risk of hope. The veterinarians are living proof that this arithmetic is wrong.

They are not confused about scale. They are not pretending that one turtle cancels out one catastrophe. They are not under the illusion that kindness is a substitute for policy. What they are doing is something both more modest and more radical: they are refusing to let the world’s enormity become an excuse to abandon the world’s particulars. Pyari is a particular. A living, breathing, slow-blinking particular.

In the hands of the people who cared for her, you can see a version of humanity that doesn’t show up much online. Not the loud humanity that performs outrage, but the quiet humanity that performs maintenance. The kind that knows survival is not just a dramatic moment, it’s a series of small, consistent decisions, made by people who show up even when nobody’s watching.

It’s feeding schedules and water quality and antibiotics. It’s cleaning tanks. It’s monitoring temperature. It’s choosing the right day for release because cold stress is real and your patient doesn’t have the luxury of a sweater. It’s the unromantic discipline of giving a damn.

And there is humor in that, too, because if you can’t laugh in a rehab center, where the stakes are high and the smells are… let’s call them “ocean-forward,” you’re going to burn out fast. I imagine the staff, bleary-eyed, doing that particular kind of gallows comedy that is actually love in disguise. “Pyari, please stop trying to bite the equipment.” “Pyari, ma’am, that is not a snack.” “Pyari, we are so proud of you, but if you flip this bucket again, I’m going to start charging you rent.” Wit is not the enemy of warmth. Sometimes it’s the handle that lets you carry it.

What does it mean to be human, anyway? We usually answer that question with grand ideals: art, language, morality, civilization. But most days, being human is much less poetic. It’s deciding whether you will be the kind of person who sees suffering and turns away, or the kind of person who sees suffering and moves toward it. It’s deciding whether you will treat the vulnerable as inconvenient, or as worthy of effort.

A turtle can’t pay you back, a turtle doesn’t vote, a turtle doesn’t write a glowing review. A turtle doesn’t even have the courtesy to look grateful. Pyari will swim out into the Atlantic and, if things go well, she will spend her days doing turtle business: diving, foraging, navigating by ancient instincts. She will not return to the Loggerhead Marinelife Center with a bouquet. She will not dedicate a wing of the building in anyone’s honor. And yet. We do not measure our humanity by the return on investment. Or at least, we shouldn’t. The best parts of us have never been transactional, they have always been, in some way, irrational: love, compassion, sacrifice, attention.

Attention is the one I keep coming back to. It’s the most endangered resource in our culture, constantly harvested, monetized, fragmented. We’re trained to look away, trained to move on, trained to skim past pain because there is always another post, another ping, another thing demanding our reaction. But those veterinarians looked closely, they kept looking, and they made the choice to stay with the problem long enough to change it. Even if the rest of the world feels like it’s falling apart, especially then, this is what steadiness looks like. Not the denial of suffering, but the refusal to let suffering have the last word. Not the fantasy of saving everything, but the practice of saving something.

On the beach, Pyari’s flippers dig into the sand. She moves forward in that awkward, determined way turtles do, as if evolution invented them on a deadline and said, “Good enough.” She reaches the edge of the water, and the waves do what waves do: they don’t clap. They don’t congratulate, they don’t pause for sentiment, they simply receive her.

And somewhere above, invisible to everyone on the shore, a satellite listens for her signal. A tiny technological thread trailing behind a creature that predates us by millions of years. Data points, yes, but also a promise: we will not stop caring the moment the story stops being convenient.

That’s the part that feels like a lifeline right now. Because the world will keep being complicated, the news will keep being heavy, and the ocean will keep being the ocean. But on one chilly Florida morning, a group of humans gathered not to gawk at disaster, but to witness recovery. They took a wounded creature, did what they could, and then did the bravest thing they could do after that: they let her go.

Not because they were sure of the ending, because they were committed to the chance. And if you’re looking for a definition of what it means to be human when everything feels frayed, when the big systems fail and the grand narratives wobble, maybe it’s this: To keep choosing care anyway, to keep choosing the particular, to keep showing up with your hands ready, your heart stubborn, and your sense of humor intact. To watch a turtle with three flippers disappear into a vast, indifferent sea, and to say, with all the quiet audacity you can muster: go on, beloved. We’re still here.

Thank you, Shanley. I think we all needed this.

Thank you.. with tears and a more open heart.