A Cold Front Moves Through Biotech

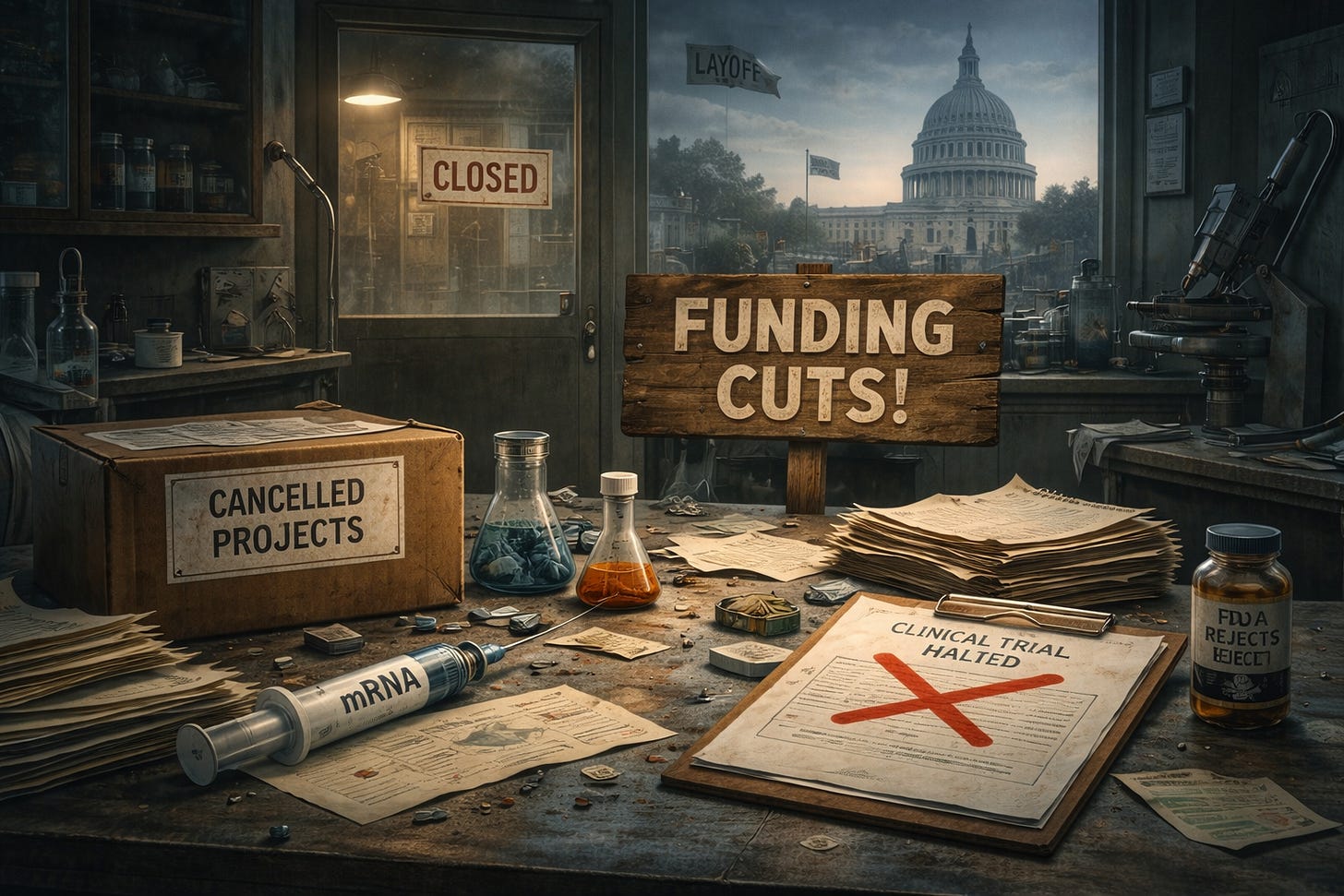

Paused trials, paused factories, and the uncomfortable realization that policy is now part of the supply chain.

The vaccine business has always been a strange hybrid of capitalism and catechism: a for-profit industry that, at its best, behaves like a public utility; a scientific enterprise whose most important customers are parents, politicians, and the pathogens themselves. For a while, the truce held. Washington paid for some of the riskiest early work, the private sector scaled it, regulators played referee, and most Americans rolled up their sleeves with the mild resentment reserved for taxes and jury duty. Then Covid arrived, mRNA became a household acronym, and everybody discovered that “public health” is not a serene technocracy but a knife fight conducted with PowerPoint.

Now the knife fight has a new emcee. The New York Times reports that vaccine executives and investors are watching the Trump administration’s approach to vaccines, under incoming Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a man who treats immunology like it’s a rumor he heard at Whole Foods, and deciding that the safest bet is to step back. Moderna is pausing parts of its infectious-disease pipeline and has watched the FDA refuse to even review its mRNA flu shot application. A small Texas outfit has put the brakes on a factory that would have brought jobs to Plano. A San Diego manufacturer has laid off workers. And the people who make vaccines, never a group famous for dramatic language, are talking openly about a chill settling over the whole sector.

What’s interesting is that this is not the usual “biotech winter” story, where the Fed raises rates and suddenly every startup CEO discovers the beauty of austerity. The Times frames it as something more specific: a political re-pricing of risk. Investors can tolerate scientific uncertainty; that’s the job, they can tolerate market uncertainty; that’s the other job. What they hate is process uncertainty, when the rules of the game look like they’re being rewritten mid-trial, ideally with a Sharpie.

Take the Moderna episode. The FDA refused to file, or refused to review, Moderna’s application for an mRNA flu vaccine, citing flaws in research design, specifically concerns about how the trial compared Moderna’s shot to existing flu vaccines, particularly for older adults. On one level, that’s banal: regulators exist to be picky, and “your comparator is wrong” is not exactly revolutionary criticism. But on another level, it’s seismic. These programs cost hundreds of millions, they are planned years in advance. If a company believes it designed a trial in alignment with the regulator, then gets told at the finish line that the regulator won’t even look at the application, that’s not just a setback, it’s a signal. The signal says the ground can move under you, and we may not tell you in time to save your ankles.

And that’s before we get to the larger policy vibe. Reporting indicates the administration has moved to cancel or wind down certain federal supports for mRNA work. At the same time, HHS has issued a sweeping update to the childhood immunization schedule, moving multiple vaccines from “routine” to “talk to your clinician,” reducing the number of diseases targeted in the default schedule. There are legitimate debates about how recommendations are set, how evidence is communicated, and how to make sure science isn’t just a priesthood. But there is also a basic economic reality: vaccine markets are unusually sensitive to default settings. For many vaccines, demand is not created by glossy advertising campaigns; it’s created by guidelines, school requirements, and insurer coverage norms. When you change the default, you change the market.

This is where the whole thing starts to resemble a sitcom written by Kafka. The administration says it isn’t discouraging innovation; it’s just being evidence-based and transparent. Fine. But evidence-based transparency still has to operate through institutions, and institutions require trust. When the top of HHS is occupied by someone whose brand is skepticism about vaccines, and who has, in the past, used rhetoric that makes virologists do the kind of long, quiet exhale usually reserved for family group texts, trust becomes a consumable resource. You can’t spend it forever.

RFK Jr. is not, as critics often caricature him, a lone weirdo shouting from the woods. He’s a powerful symbol in a culture war where vaccines are no longer just a medical product but a moral referendum. The Times quotes Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla describing vaccines as an area where politics starts to feel like religion. You don’t have to like Bourla to see what he means: vaccination has become a proxy for who you are, who you distrust, and which elites you imagine are plotting in your pantry.

And like any religion, it has schisms. One schism is between those who think mRNA is a modern miracle, fast to design, adaptable, scalable, and those who think it’s a sci-fi experiment conducted on the innocent by Pfizer’s HR department. The scientific record on mRNA Covid vaccines is not subtle: they do not perfectly prevent infection, especially as variants evolve, but they did significantly reduce severe disease and death, and serious adverse events are rare. If your critique is “they didn’t end Covid forever,” congratulations, you have discovered reality, medicine is not a Marvel movie.

The business question, though, is less about what’s true in journals and more about what’s bankable in boardrooms, Moderna’s whole corporate identity is mRNA. If the federal government is perceived as hostile to the platform, or even just unpredictably skeptical, Moderna’s pipeline becomes riskier by definition. The Times points out that Moderna is continuing late-stage work in cancer, but pausing late-stage infectious-disease efforts, including promising Epstein-Barr virus vaccines. That’s not because Moderna suddenly stopped believing in viruses. It’s because the company is doing what companies do: triaging programs based on the likelihood they’ll survive both the lab and the politics.

This is also where the jobs story matters. Politicians love to talk about bringing manufacturing back to the United States. “Reshore” is the kind of word that makes consultants salivate and governors pose in hard hats. But vaccine manufacturing is not a simple “build factory, make widgets” project. It depends on stable demand, stable regulations, stable liability frameworks, and stable procurement. If you make the product politically radioactive, you don’t just slow innovation. You discourage the boring, expensive physical infrastructure that every administration claims to want. Plano doesn’t lose jobs because viruses have stopped existing; it loses jobs because uncertainty is contagious too.

The Times also hints at the larger boogeyman: liability. Vaccine makers in the U.S. operate under special liability protections that were created because, without them, the litigation risk would scare companies out of the market. If those protections were weakened, the economics could change overnight, not in a “we’ll adapt” way, but in a “we’re leaving” way. Even speculation about changes can spook investors, because the expected value of a vaccine portfolio depends on not being sued into the earth for doing exactly what the government asked you to do.

To be clear, the vaccine industry is not a choir of angels. It has made marketing mistakes, communications mistakes, and occasionally the sort of executive decisions that suggest the C-suite spends too much time inhaling its own press releases. The Times acknowledges that vaccine sales have been declining for reasons that predate Kennedy: rising hesitancy, post-pandemic fatigue, a general cultural turn toward “I did my own research,” which usually means “I watched a man in a truck explain immunology.” The flu shot market, in particular, has been sliding, and Covid boosters are now treated by many Americans like printer software updates: they know they should do it, they swear they’ll do it later, and eventually they ignore the reminder until something breaks.

But that’s precisely why political whiplash is so potent here. Vaccines already operate on thin margins of public trust and modest profits for many routine products. When demand is fragile, the last thing you want is the federal government sending mixed signals that look, to the public, like confirmation that something is fishy. If the head of HHS speaks as if the scientific consensus is suspicious by default, it doesn’t matter how many times a spokesperson says “we’re not anti-science.” The messenger matters. And this messenger has spent years auditioning for the role of “America’s most influential guy at the PTA meeting who forwards you a PDF.”

So, what happens next? Probably not an immediate collapse. Big pharma can absorb a lot. Merck, Pfizer, GSK, Sanofi, vaccines are important, but most of their revenue is elsewhere. The more acute pain is at the edges: smaller manufacturers, platform companies, startups who need a friendly regulatory climate and the promise of reimbursement to justify venture funding. If those firms pull back, the pipeline thins. Then five or ten years from now, when a new pathogen pops up or an old one evolves, we discover, again, that society loves vaccines the way it loves firefighters: it resents paying for them until the moment it desperately needs them.

The tragedy, is that there’s room for a serious conversation about vaccine policy that doesn’t involve torches and pitchforks. We can debate evidence thresholds, trial design, booster strategy, and risk communication without turning the entire enterprise into performance art. But that requires leaders who can distinguish skepticism from sabotage. You can ask hard questions without implying that everyone is lying. You can demand transparency without encouraging cynicism. You can run HHS without sounding like your Google search history is trying to unionize.

If the Times is right, the early signs are already here: paused trials, paused factories, laid-off workers, skittish investors, and executives quietly asking whether the United States still wants to be in the vaccine business at all. That would be an odd choice for a country that prides itself on innovation, preparedness, and saving lives, unless, of course, we’ve decided that the real enemy isn’t disease, but the people who tried to stop it.

Everyone should heed Bobby Brainworm when he says "no one should take medical advice from him". Amen to that.

There was a political blog that was an offshoot of Daily Kos. It was called Caucus99%. Caucus99% was started by a group of former Kos members who were either disenchanted with mainstream Democrats like Nancy Pelosi and tired of either watching or experiencing the policy that Kos had of banning people who expressed support for the more left wing progressive side of the party. I joined Caucus99%. It went well until anti vax postings became a thing during COVID, to the point that the owner let those discussions have their own portion of the postings. It went further than that. Anyone who argued against the JFK Jr. side of things (like me) was pushed to the corner and verbally attacked. The owner of the site did nothing about it and eventually started banning the pro vax people. In the meantime more posts were becoming pro-Tulsi Gabbard and anti-Ukraine (pro- Putin). I was basically watching the MAGA portion of our politics take over a formerly left wing progressive site. So I would agree that JFK Jr is not just some lone wolf howling at the moon. His minions have been infiltrating our national dialogue for a long time.